Scroll to:

A parallel arm randomised controlled trial to achieve remission in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus through dietary and behavioural interventions: a study protocol

https://doi.org/10.47093/2218-7332.2025.1097.18

Abstract

Background. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) poses a significant challenge to healthcare, with its prevalence escalating to epidemic proportions. The aging population, coupled with the increasing burden of T2DM, is exerting immense pressure on healthcare systems worldwide. Therefore, there is a critical need to design and validate innovative interventions to mitigate the effects of this disease. This randomised control trial aims to achieve remission in Indian patients aged 18 years and older diagnosed with T2DM through dietary and behavioural interventions.

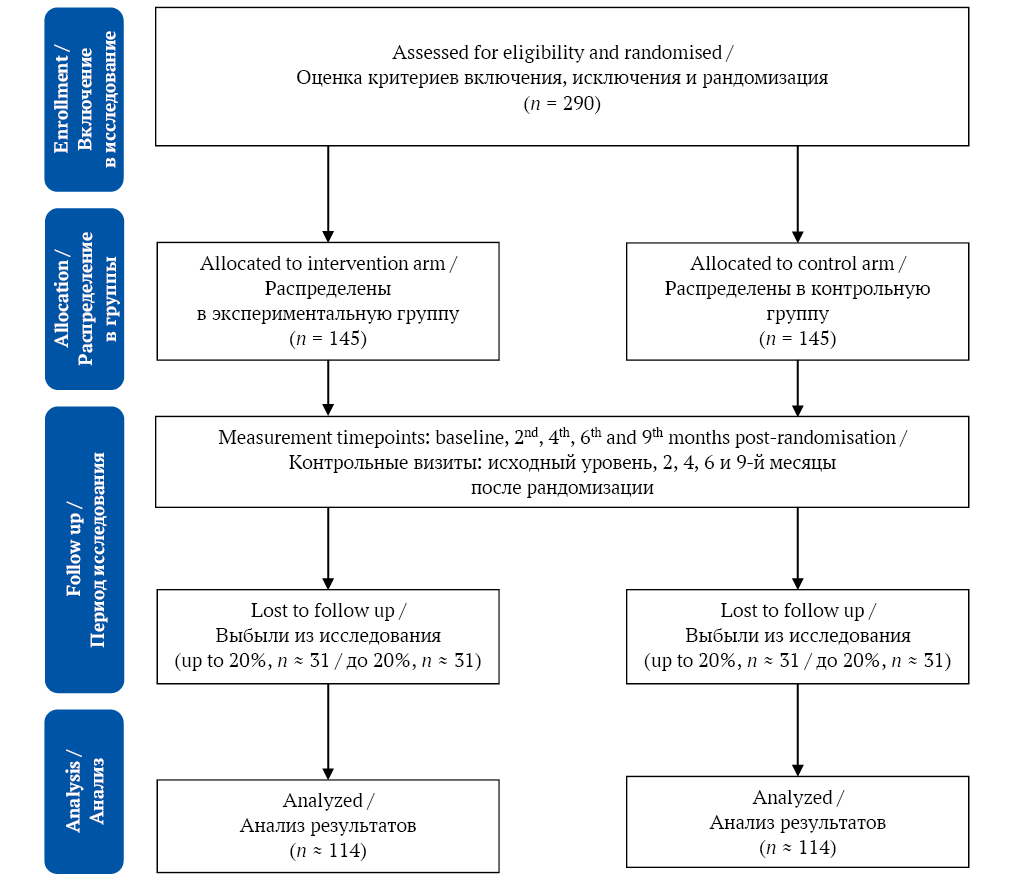

Materials and methods. A total of 290 participants with T2DM will be recruited from Indira Colony Urban Enclave, the field practice area of the Department of Community Medicine and School of Public Health at Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh. Participants will be equally allocated into two arms: intervention (n = 145) and control (n = 145). There will be five measurement timepoints: baseline, 2nd, 4th, 6th and 9th months postrandomisation. The intervention will implement a range of strategies to increase physical activity and promote dietary transitions through behaviour change among patients. The interventions will be designed ensuring a structured approach to behaviour change. Patients from the intervention arm will receive oral hypoglycaemic agents for the first six months of the trial. After this period, medication will be gradually tapered. Patients from the control arm will continue to receive standard care throughout the study. The primary outcome is the number of patients achieving remission of T2DM through behavioural and dietary interventions.

Conclusions. The novelty of this trial lies in its focus on community-based settings, unlike other studies that primarily target clinical or hospital-based environments to achieve clinical outcomes. The intervention integrates dietary and behavioural changes into the community’s cultural, socioeconomic, and dietary habits, making it practical and sustainable for patients to adopt and maintain the lifestyle changes needed for remission.

Keywords

BACKGROUND (6a)

Non-communicable diseases (NCD) are the leading cause of death globally and disproportionately affect individuals in low- and middle-income countries, where they account for 80% of all deaths and 90% of premature deaths.3 In absolute terms, out of 56 million global deaths, 38 million (67.8%) are directly attributable to NCD [1].

According to the ICMR-INDIAB study the prevalence of diabetes in India is 7.3% with a wide regional and an urban-rural variation [2]. Given this context, the economic burden of managing NCD and their complications poses a substantial challenge for policymakers when allocating resources and funds for their diagnosis and treatment. The challenge is exacerbated by the need to prioritize funding for traditional public health concerns, such as communicable diseases and maternal and child health, which remain at the top of the agenda. This prioritization further strains the limited resources available [3][4].

The rationale for conducting the study

As life expectancy rises, India faces a dual health challenge: widespread communicable diseases alongside the growing burden of NCD compounded by an aging population and strained healthcare infrastructure [5]. Evidence suggests that lower socioeconomic groups are more prone to alcohol and tobacco use and insufficient consumption of fruits and vegetables, increasing their NCD risk [6].

Management of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and other lifestyle diseases has relied on pharmacological interventions, like oral hypoglycaemic agents (OHAs) to achieve normoglycaemia [7]. Along with medication treatment lifestyle changes are integral components of achieving T2DM remission. Recent evidence such as from the DiRECT Trial, highlights the potential for T2DM remission through structured weight management programs [8][9]. However, these findings need to be validated in a number of diverse settings, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where data is limited to case reports [10]. The study evaluating the effects of dietary and behaviour interventions in achieving remission in patients with T2DM in low- and middle-income countries is acutely needed in order to develop a more efficient strategy for these patients.

The rationale behind choosing dietary and behaviour interventions to achieve remission in patients with T2DM (6b)

Lifestyle changes have a positive impact on managing T2DM. In a retrospective review the complete and partial remission rates in patients 6 years after bariatric surgery were found to be 24% and 26% respectively [11]. By contrast, another study showed that weight loss through calorie restriction can also induce remission of T2DM in a dose-dependent manner, with a 15kg reduction achieving remission in 80% of patients [12]. Moreover, weight loss is cost effective and could significantly reduce out-of-pocket expenses on medications and laboratory tests [13].

In low- and middle-income countries such as India, dietary and behavioural interventions are favoured for achieving remission in patients with T2DM due to their cost-effectiveness, feasibility, and accessibility. Regular physical activity plays a crucial role by enhancing glucose uptake by skeletal muscles, improving insulin sensitivity, and facilitating weight management. Our hypothesis is that a combination of diet and exercises, tailored to the patient’s lifestyle and activity level, will contribute to achieving T2DM remission. Our core focus is based on three outcomes: (1) aerobics exercises (brisk walking, jogging) to boost endurance; (2) yoga to improve flexibility [14]; (3) resistance exercises to enhance strength.

The rational for choosing a low carbohydrate diet (6b)

The ICMR (Indian Council of Medical Research) 2018 guidelines for patients with T2DM recommend consuming 55–60% of energy from carbohydrates, prioritizing complex over refined carbohydrates.4 This dietary approach aims to improve glycaemic control by regulating caloric intake, optimizing macronutrient distribution, and promoting fibre-rich foods. Based on ICMR-NIN (Indian Council of Medical Research National Institute of Nutrition) 2024 guidelines, patients will receive tailored diets focusing on balanced nutrition, with specific energy and macronutrient recommendations for individuals below and above 60 years.5

Traditional Indian diets, mainly rice- and wheat-based, should be reconsidered due to the rising burden of T2DM and other NCD in India [15]. Millets such as finger millet (ragi), pearl millet (bajra), and foxtail millet, have a low glycaemic index, leading to a gradual rise in blood glucose levels essential for T2DM management. Rich in fibre, protein, and essential nutrients like magnesium and iron, millets improve satiety, enhance insulin sensitivity, and support gut health [16][17], establishing their value in T2DM dietary strategies.6

The rationale for a 9-month follow-up period

A 9-month follow-up period was selected based on the study design. Weight loss through dietary interventions tends to be slower than achieved via bariatric surgery. Kim et al. showed that sustained lifestyle changes can lower glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) within 6 months [18]. With regular monitoring and gradual tapering of OHAs based on glycaemic status, significant outcomes are expected within 9 months. This timeframe also balances clinical relevance with practicality, reducing dropout rates while preserving data quality and participant engagement.

Objectives (7)

Primary objective

To evaluate the effect of dietary and behavioural interventions in achieving remission in patients diagnosed with T2DM.

Secondary objectives

- To assess patients’ acceptability of adopting dietary and behavioural interventions through in-depth interviews.

- To evaluate the impact of dietary interventions on patients with T2DM having co-morbidity such as arterial hypertension.

Trial design (8)

The study is a parallel two-arm randomised control trial (allocation ratio 1:1). Patients will be randomised into an intervention arm (dietary and behavioural intervention) and a control arm receiving standard care (fig.). There will be five measurement timepoints: baseline, 2nd, 4th, 6th and 9th months post-randomisation.

FIG. Study flowchart.

РИС. Потоковая диаграмма исследования.

METHODS

Study setting (9)

The 9-month community based randomised control trial will implement dietary and behavioural interventions for adults ≥18 years with T2DM in the Indira Colony Urban Enclave, the field practice area of the Department of Community Medicine and School of Public Health at Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research Chandigarh [19], Northern India, with a population of 25,000 as per the census conducted in 2011.7 The sampling frame comprises T2DM cases from a 2018 house-to-house survey (unpublished). Considering changes in morbidity and mortality, investigators will update the database through a new house-to-house survey.

Inclusion criteria (10)

- Confirmed diagnosis of T2DM per HEARTS-D module criteria.8

- Age ≥18 years.

- Patients providing informed consent (26a).

- Patients with systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and / or diastolic blood pressure ≥90mm Hg as per 2016 primary hypertension guidelines by India’s Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.9

Exclusion criteria

- Patients not providing informed consent.

- Patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus.

- Age < 18 years.

- Patients with impaired fasting glucose and glucose tolerance.10

- Insulin-treated patients.

Definition of remission

Diabetes remission is defined using specific HbA1c, fasting, and postprandial glucose thresholds maintained without OHAs. The American Diabetes Association classifies remission as complete, partial, or prolonged [20]. The Association of British Clinical Diabetologists and Primary Care Diabetes Society define remission as glycaemia below diagnostic thresholds for ≥6 months without glucose-lowering therapy [21]. This study adopts the American College of Lifestyle Medicine’s definition: HbA1c < 6.5% for at least 3 months without surgery, external devices, or active glucose-lowering medication [22].

Intervention (11a)

Intervention arm

Customised diet plan per Dietary Guidelines11

Carbohydrate intake will be restricted to <50% of total calories, replaced with fibre-rich, non-starchy foods and green leafy vegetables, alongside increasing vegetable salads in the diet [23]. Millet will be incorporated flexibly into participants’ diets as porridge, chapati (Indian millet flat bread), or traditional Indian millet snacks. While millet will not fully replace other grains, it will be promoted as a healthier alternative, prioritized over refined grains like white rice and refined wheat. The intervention aims to shift dietary patterns toward millet-based options as a primary grain.

Physical activity plan

Physical activity recommendations are tailored to the patient’s fitness level, age, and any physical limitations.12 Exercise plans will be customised according to patient’s age. For patients who undertake a moderate amount of activity, the regimen will aim to sustain their activity through aerobic exercises, resistance training, and yoga. For sedentary patients, a gradual initiation into physical activity will be encouraged, starting with light exercises such as walking. Progress will be closely monitored, and plans will be adjusted based on patient response. Daily activity charts will be provided to track time spent on physical exercises.

Standard medication

Patients will receive OHAs for the first six months of the trial. After this period, OHAs will be gradually tapered for patients with HbA1c levels below 6.5%. Patients weaned off OHAs will monitor blood glucose levels using finger-prick tests. If any patient struggles with the reduced dosage, their original medication regimen will be reinstated. The day a patient is completely weaned off OHAs marks the start of a three-month follow-up period. Patients showing symptoms of dysglycaemia will be reviewed and consulted with an endocrinologist to determine whether OHAs should be resumed.

The package of intervention in our study is summarised in Table.

Table. Summary of dietary and behaviour interventions

Таблица. Резюме диетических и поведенческих вмешательств

|

Intervention / Вмешательство |

Package under each intervention / Компоненты каждого вмешательства |

|

Dietary14 / Диета14 |

(a) Introduction of millet-based diet that is low in carbohydrate and energy / Введение диеты на основе проса с низким содержанием углеводов и энергии (b) Encouraging the consumption of five servings of fruits and vegetables daily / Выработка привычки ежедневного потребления пяти порций фруктов и овощей (c) Limiting free sugars intake to less than 10% of total energy consumption / Ограничение потребления легкоусвояемых углеводов до 10% от суточной калорийности рациона (d) Reduction of fat intake to less than 30% of energy consumption / Ограничение потребления жиров до 30% от суточной калорийности рациона (e) Distribution of millet food baskets to patients / Снабжение пациентов продовольственными корзинами с просом |

|

Behavioural / Изменение образа жизни |

(a) Community engagement by organising community based events and workshops that promote physical activity, using a support network as a central pillar / Вовлечение сообщества путем организации местных мероприятий и семинаров, пропагандирующих физическую активность, с использованием социальной сети для поддержки (b) Culturally tailored messaging derived through vertical and horizontal communication channels / Информирование с учетом культурных особенностей по вертикальным и горизонтальным каналам связи (c) Addressing barriers to physical activity by conducting focus group discussions and offering targeted solutions to the challenges identified [24] / Устранение препятствий для физической активности путем обсуждений в фокус-группах и разработки решений выявленных проблем [24] (d) Implement an incentive programme to motivate patients to maintain regular physical activity and adhere to dietary interventions / Внедрение мотивационной программы для поддержания регулярной физической активности и соблюдения диетических ограничений (e) Establish community-based yoga groups and promote specific yoga poses known to benefit patients with T2DM / Создание общественных групп йоги для продвижения движений, оказывающих положительное влияние на пациентов с СД2 |

Note: T2DM – type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Примечание: СД2 – сахарный диабет 2-го типа.

Control arm

Patients in control arm will continue to receive OHAs as prescribed by their physician. No dietary and behavioural interventions will be made in the control arm.

Participant timeline (13)

At each timepoint, HbA1c, waist circumference, weight and body mass index will be measured.

Additionally for patients in the intervention group, investigators will conduct weekly visits to address challenges in adopting lifestyle changes, monitor diet adherence, review self-recorded capillary blood glucose diaries, and provide personalized support. A WhatsApp group will be created for participants in the intervention arm, where investigators will share motivational voice notes and video vlogs to encourage adherence.

Data collection will include a peer-reviewed, Delphi-validated questionnaire designed with input from subject experts to capture demographic profiles and dietary habits through a Food Frequency Questionnaire, assessing daily and weekly consumption patterns [25]. Additional tools include questions to identify barriers and facilitators of healthy dietary and physical activity transitions, the World Health Organisation STEPS (STEPwise approach to NCD risk factor surveillance) questionnaire for dietary and physical history,13 and the EuroQol EQ-5D-5L questionnaire for quality of life assessment [26].

Criteria for discontinuing the trial (11b)

Parents may withdraw from the trial at any time without prejudice or in case of frequent episodes of hypoglycaemia.

Strategies to improve adherence to the study protocol (11c)

Informative booklets and pamphlets with colourful info graphics will address local dietary habits, cultural beliefs, and misconceptions about T2DM, offering practical guidance on diet and exercise in simple, engaging language. Adherence cards will be provided to each patient in the intervention arm to help track physical activity, monitor dietary patterns, and make adjustments as needed.

To enhance compliance, investigators will conduct weekly visits to review adherence cards, providing constructive feedback to both patients and their family champions on gaps and strategies to achieve targets. This approach emphasizes open, two-way communication. The term family champion refers to a key family member who actively supports the participant during the study in adhering to dietary and behavioural interventions. This role is crucial in fostering accountability, motivation, and creating a supportive home environment, which is essential for sustainable lifestyle changes and effective T2DM management.

The selection of the family champion follows four key principles:

- Emotional and practical support. The family champion provides encouragement, assists with meal planning, and supports daily routines, improving adherence to lifestyle changes.

- Close relationship with the patient. Ideally a spouse, sibling, or adult child with a trusting bond, empathy, and open communication to provide reliable support.

- Consistency and accountability. A consistent presence, the family champion helps maintain adherence by gently reminding patients of the importance of prescribed interventions.

- Cultural and household dynamics. In Indian households where families play a central role in health decisions, the family champion leverages this cultural strength, embedding support within the broader family network.

The intervention includes focus group discussions to enhance social support by encouraging the sharing of challenges and successes, peer influence through positive behaviour, group norms to establish shared expectations, accountability via regular check-ins, shared goals by celebrating achievements, and collaborative problem-solving to address barriers effectively.

Sample Size (14)

The total recruitment target is 228 patients (114 per arm), calculated with a 95% confidence interval and 80% power. The sample size estimation was based on a study reporting remission rates of 57% in patients with T2DM following dietary intervention, compared to 31% in the control group [27]. Accounting for a 20% non-response rate, the adjusted sample size was calculated as 285. However, for simplicity, a sample size of 290 (145 per arm) was chosen. The calculation was performed using OpenEPI software, version 3, for a randomised control trial.

Recruitment of participants (15)

The first step involves baseline recruitment where investigators will visit households to enroll patients in the trial. To prevent contamination bias [28], only patients who provide informed consent will be recruited.

Allocation (16a) and concealment (16b) of participants will be managed through sealed envelopes, with a neutral third party assigning patients to each trial arm. The initial recruitment will include all 290 patients, followed by block randomisation in blocks of 4, 6 and 8 into either of the arm. Varying block sizes was shown to have several advantages over one single block including increased unpredictability of the allocation sequence, thereby reducing selection bias. This approach minimizes risks of manipulation or subversion of the allocation process, enhancing the trial’s integrity and robustness.

Outcome measures (12)

Primary outcome

The number of patients achieving remission of T2DM through behavioural and dietary interventions.

Secondary outcomes

- The number of patients with hypertension as co-morbidity achieving normal blood pressure.

- Assessment of acceptability and identification of barriers to adopting dietary interventions, particularly the inclusion of millets.

Data collection (18)

Demographic data, medication information, clinical symptoms, data on primary and secondary outcomes, laboratory tests (fasting and post prandial blood glucose, HbA1c), physical examinations (weight, body mass index, waist circumference), and validated questionnaires assessing dietary intake, quality of life will be collected at each timepoints. For promoting data quality outcome measurements will be taken by using pre-formulated standardized protocols. To minimize measurement error, duplicate measurements will be taken where applicable (e.g., blood pressure), and the average of the readings will be recorded.

Statistical methods (20)

Data analysis will be performed using IBM SPSS version 25 (released 2017, IBM Corp., USA).

Statistical methods for analysing primary and secondary outcomes (20a)

Univariate analysis will be conducted to compare the demographic data of patients in the intervention and control groups. McNemar’s test or paired t-tests will be performed for pre- and post-intervention comparisons in patients with arterial hypertension. A logistic regression model will be utilized to identify factors associated with blood pressure normalization. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis will be performed to estimate the proportion of patients achieving remission over time, with remission treated as a time-dependent variable at the 9th month.

Methods for additional analyses (20b)

We will conduct focus group discussions and semi-structured interviews to explore patients’ perceptions of dietary changes, particularly concerning millet consumption. Content or thematic analysis will be used to identify common barriers, including cost, accessibility, taste, or unfamiliarity with millets.

Subgroup and adjusted analyses

A separate analysis of primary outcome and effect estimates will be performed for physical activity level, gender, age, and fruit and vegetable intake.

Confidentiality (27)

Data confidentiality will be ensured through de-identification and anonymization, with minimal use of identifiers. Prior to collecting any personal data, written informed consent will be obtained from participants. During this process, participants will be informed about the type of the data to be collected, its intended use, and the measures implemented to protect their privacy.

Declaration of interests (28)

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the trial.

Access to data (29)

The principal investigator will be custodian of the data. In the trial, access to the final dataset will be managed to ensure both data integrity and participant confidentiality.

DISCUSSION

Achieving remission in T2DM requires a comprehensive management plan alongside OHAs treatment. This includes the supervised and systematic de-prescription of existing antihyperglycaemic medications and the gradual introduction of lifestyle changes, such as a calorie-restricted diet supplemented with a millet-based component [29]. We propose that T2DM remission is an achievable clinical goal. Our study gains relevance from its alignment with the declaration of 2023 as the International Year of Millets, focusing on this “wonder grain”.15

However, challenges exist regarding the acceptance of millets among participants. These include an underdeveloped supply chain, limited availability in retail outlets, higher costs compared to rice and wheat [30], and societal perceptions that undervalue millets as an investment in future health [31]. Despite these barriers, we anticipate significant improvements in participants’ quality of life upon achieving remission. Benefits may include enhanced mental and physical health, fewer work-loss days, reduced hospitalizations, and potentially lower risks of complications associated with T2DM [32][33].

The novelty of this trial lies in its community-based approach, diverging from the typical clinical or hospital-based frameworks. By leveraging accessible and sustainable interventions, it empowers T2DM patients to pursue remission. The intervention integrates dietary and behavioural changes into the cultural, socioeconomic, and dietary contexts of the community, facilitating the adoption and long-term maintenance of lifestyle changes essential for remission.

Ethics statements. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics committee of Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh (approval number: INT/IEC/2024/SPL-67 dt 12th February 2024).

Conflict of interests. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Trial registration information

Note: the numbers in round brackets in this protocol refer to SPIRIT checklist item numbers.1

|

Title (1) |

A parallel arm randomised controlled trial to achieve remission in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus through dietary and behavioural interventions: a study protocol |

|

Trial registration (2a) |

REF/2024/02/079325 (Clinical Trial Registry of India) |

|

Protocol version (3) |

12th February 2024, version 1 |

|

Funding (4) |

The study is not sponsored (own resources) |

|

Author details (5a) |

Singh A., Thakur J.S. (contact details are above) |

Соблюдение этических норм. Протокол исследования одобрен Этическим комитетом Института постдипломного медицинского образования и исследований, г. Чандигарх (№ INT/IEC/2024/SPL-67 от 12 февраля 2024 г.).

Конфликт интересов. Авторы заявляют об отсутствии конфликта интересов.

Информация о регистрации клинического исследования

Примечание: числа в круглых скобках в тексте протокола относятся к номерам пунктов чек-листа SPIRIT2.

|

Название (1) |

Рандомизированное контролируемое исследование в параллельных группах по достижению ремиссии у пациентов с сахарным диабетом 2-го типа через диетические и поведенческие вмешательства: протокол исследования |

|

Регистрационный номер (2a) |

REF/2024/02/079325 (Регистр клинических исследований Индии) |

|

Версия протокола (3) |

12 февраля 2024, версия 1 |

|

Финансирование (4) |

Исследование не имеет спонсорской поддержки (собственные ресурсы) |

|

Информация об авторах (5a) |

Сингх А., Тхакур Дж.С. (контактная информация указана выше) |

1 SPIRIT 2013 Statement: Defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Accessed October 04, 2024. https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/spirit-2013-statement-defining-standard-protocol-items-for-clinical-trials/

2 SPIRIT 2013 Statement: Defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Accessed October 04, 2024. https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/spirit-2013-statement-defining-standard-protocol-items-for-clinical-trials/

3 World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. 265 р. ISBN: 9789241564854. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564854

4 Indian Council of Medical Research. Guidelines for Management of Type 2 Diabetes. 2018. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://www.icmr.gov.in/icmrobject/custom_data/pdf/resource-guidelines/ICMR_GuidelinesType2diabetes2018_0.pdf

5 Indian Council of Medical Research. Dietary Guidelines for Indians. 2024. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://www.nin.res.in/dietaryguidelines/pdfjs/locale/DGI07052024P.pdf

6 International Diabetes Federation. Clinical Practice Recommendations for managing Type 2 Diabetes in Primary Care. 2017. Accessed January 14, 2024. https://idf.org/media/uploads/2023/05/attachments-63.pdf

7 Census of India 2011 – Chandigarh UT – Series 05 – Part XII A – District Census Handbook, Chandigarh. 2014. Accessed January 15, 2024. https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/324

8 World Health Organization. HEARTS D: diagnosis and management of type 2 diabetes. 2020. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-ucn-ncd-20.1

9 Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. Screening, Diagnosis, Assessment, and Management of Primary Hypertension in Adults in India. 2016. Accessed January 11, 2024. https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/guidelines/nrhm-guidelines/stg/Hypertension_full.pdf

10 Indian Council of Medical Research. Guidelines for Management of Type 2 Diabetes. 2018. Accessed January 13, 2024. https://www.icmr.gov.in/icmrobject/custom_data/pdf/resource-guidelines/ICMR_GuidelinesType2diabetes2018_0.pdf

11 Indian Council of Medical Research. Dietary Guidelines for Indians. 2024. Accessed January 20, 2024. https://www.nin.res.in/dietaryguidelines/pdfjs/locale/DGI07052024P.pdf

12 Fit India Mission. Fitness Protocols and Guidelines for 18+ to 65 Years. Accessed January 18, 2024. https://yas.nic.in/sites/default/files/Fitness%20Protocols%20for%20Age%2018-65%20Years%20v1%20(English).pdf

13 World Health Organization. The WHO STEPwise approach to surveillance. 2021. Accessed January 15, 2024. https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/WHO-EURO-2021-2446-42201-58182

14 World Health Organization. Healthy diet. Accessed January 15, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet

15 Malleshi N. Finger millet (ragi) – the wonder grain. FoodInfo Online Features. 2004. Accessed January 25, 2024. http://ir.cftri.res.in/id/eprint/12640

References

1. Roth G.A., Abate D., Abate K.H., et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 2018 Nov; 392(10159): 1736–1788. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)32203-7. PMID: 30496103

2. Anjana R.M., Deepa M., Pradeepa R., et al. Prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes in 15 states of India: results from the ICMRINDIAB population-based cross-sectional study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017 Aug; 5(8): 585–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30174-2. PMID: 28601585

3. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. Strategies for reducing morbidity and mortality from diabetes through health-care system interventions and diabetes self-management education in community settings. A report on recommendations of the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001 Sep 28; 50(RR-16): 1–15. PMID: 11594724

4. Nugent R. A Chronology of Global Assistance Funding for NCD. Glob Heart. 2016 Dec 1; 11(4): 371–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gheart.2016.10.027. PMID: 27938820

5. Sahoo P.M., Rout H.S., Jakovljevic M. Consequences of India’s population aging to its healthcare financing and provision. J Med Econ. 2023 Feb 23; 26(1): 308–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2023.2178164. PMID: 36780290

6. Vellakkal S., Subramanian S.V., Millett C., et al. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Non-Communicable Diseases Prevalence in India: Disparities between Self-Reported Diagnoses and Standardized Measures. PLoS One. 2013 Jul 15; 8(7): e68219. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068219. PMID: 23869213

7. Ke C., Narayan K.M.V., Chan J.C.N., et al. Pathophysiology, phenotypes and management of type 2 diabetes mellitus in Indian and Chinese populations. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022 Jul; 18(7): 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-022-00669-4. Epub 2022 May 4. PMID: 35508700

8. Uusitupa M. Remission of type 2 diabetes: mission not impossible. The Lancet. 2018 Feb 10; 391(10120): 515–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)33100-8. Epub 2017 Dec 5. PMID: 29221646

9. Lean M.E., Leslie W.S., Barnes A.C., et al. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. The Lancet. 2018 Feb 10; 391(10120): 541–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(17)33102-1. PMID: 29221645

10. Dixit J.V., Giri P.A., Badgujar S.Y. `Daily 2-only meals and exercise’ lifestyle modification for remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A therapeutic approach. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022 Sep; 11(9): 5700–5703. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_129_22. PMID: 36505570

11. Brethauer S.A., Aminian A., Romero-Talamás H., et al. Can diabetes be surgically cured? Long-term metabolic effects of bariatric surgery in obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 2013 Oct; 258(4): 628–637. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0b013e3182a5034b. PMID: 24018646

12. Magkos F., Hjorth M.F., Astrup A. Diet and exercise in the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020 Oct; 16(10): 545–555. Epub 2020 Jul 20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-020-0381-5. PMID: 32690918

13. Xin Y., Davies A., Briggs A., et al. Type 2 diabetes remission: 2 year within-trial and lifetime-horizon cost-effectiveness of the Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial (DiRECT)/Counterweight-Plus weight management programme. Diabetologia. 2020 Oct; 63(10): 2112–2122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-020-05224-2. Epub 2020 Aug 10. PMID: 32776237

14. Kaur N., Majumdar V., Nagarathna R., et al. Diabetic yoga protocol improves glycemic, anthropometric and lipid levels in high risk individuals for diabetes: a randomized controlled trial from Northern India. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2021 Dec 23; 13(1): 149. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-021-00761-1. PMID: 34949227

15. Mohan V., Radhika G., Sathya R.M., et al. Dietary carbohydrates, glycaemic load, food groups and newly detected type 2 diabetes among urban Asian Indian population in Chennai, India (Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study 59). Br J Nutr. 2009 Nov; 102(10): 1498–1506. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114509990468. Epub 2009 Jul 9. Erratum in: Br J Nutr. 2010 Jun;103(12):1851-2. PMID: 19586573

16. Kam J., Puranik S., Yadav R., et al. Dietary interventions for type 2 diabetes: how millet comes to help. Front Plant Sci. 2016 Sep 15 Malleshi N. Finger millet (ragi) – the wonder grain. FoodInfo Online Features. 2004. Accessed January 25, 2024. http://ir.cftri.res.in/id/eprint/1264027; 7: 1454. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.01454. PMID: 27729921

17. Anitha S., Kane-Potaka J., Tsusaka T.W., et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the potential of millets for managing and reducing the risk of developing diabetes mellitus. Front Nutr. 2021 Jul 28; 8: 687428. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.687428. PMID: 34395493

18. Kim J., Hur M.H. The Effects of dietary education interventions on individuals with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Aug 10; 18(16): 8439. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168439. PMID: 34444187

19. Kathirvel S., Jeyashree K., Patro B.K. Social mapping: a potential teaching tool in public health. Med Teach. 2012; 34(7): e529–531. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2012.670321. Epub 2012 Mar 28. PMID: 22452276

20. Buse J.B., Caprio S., Cefalu W.T., et al. How do we define cure of diabetes? Diabetes Care. 2009 Nov; 32(11): 2133–2135. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-9036. PMID: 19875608

21. Nagi D., Hambling C., Taylor R. Remission of type 2 diabetes: a position statement from the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) and the Primary Care Diabetes Society (PCDS). British Journal of Diabetes. 2019 Jun 27; 19(1): 73–76. https://doi.org/10.15277/bjd.2019.221

22. Kelly J., Karlsen M., Steinke G. Type 2 diabetes remission and lifestyle medicine: a position statement from the American College of lifestyle medicine. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2020 Jun 8; 14(4): 406–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827620930962. PMID: 33281521

23. Viswanathan V., Krishnan D., Kalra S., et al. Insights on medical nutrition therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus: an indian perspective. Adv Ther. 2019 Mar; 36(3): 520–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-0872-8. Epub 2019 Feb 7. PMID: 30729455

24. Hennink M.M., Leavy P. Understanding focus group discussions. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199856169.001.0001. ISBN: 9780199856169

25. Thangaratinam S., Redman C.W. The Delphi technique. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist. 2005 Apr; 7(2): 120–125. https://doi.org/10.1576/toag.7.2.120.27071

26. Jyani G., Sharma A., Prinja S., et al. Development of an EQ5D Value Set for India Using an Extended Design (DEVINE) Study: The Indian 5-Level Version EQ-5D Value Set. Value Health. 2022 Jul; 25(7): 1218–1226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2021.11.1370. Epub 2022 Jan 5. PMID: 35779943

27. Goldenberg J.Z., Day A., Brinkworth G.D., et al. Efficacy and safety of low and very low carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes remission: systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished randomized trial data. BMJ. 2021 Jan 13; 372: m4743. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4743. PMID: 33441384

28. Hemming K., Taljaard M., Moerbeek M., et al. Contamination: How much can an individually randomized trial tolerate? Stat Med. 2021 Jun7; 40(14): 3329–3351. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.8958. Epub 2021 May 7. PMID: 33960514

29. Jin S., Bajaj H.S., Brazeau A.S., et al. Remission of type 2 diabetes: user’s guide. Can J Diabetes. 2022 Dec; 46(8): 762–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2022.10.005. Epub 2022 Nov 11. PMID: 36567080

30. Pandey A., Bolia N.B. Millet value chain revolution for sustainability: A proposal for India. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences. 2023 Jun; 87: 101592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2023.101592

31. Erler M., Keck M., Dittrich C. The changing meaning of millets: Organic shops and distinctive consumption practices in Bengaluru, India. Journal of Consumer Culture. 2020 Jan 27; 22(1): 124–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540520902508

32. Lichtenstein G.R., Yan S., Bala M., Hanauer S. Remission in patients with Crohn’s disease is associated with improvement in employment and quality of life and a decrease in hospitalizations and surgeries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Jan; 99(1): 91–96. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1572-0241.2003.04010.x. PMID: 14687148

33. Banerji M.A., Chaiken R.L., Lebovitz H.E. Long-term normoglycemic remission in black newly diagnosed NIDDM subjects. Diabetes. 1996 Mar; 45(3): 337–341. https://doi.org/10.2337/diab.45.3.337. PMID: 8593939

About the Authors

A. SinghIndia

Arunjeet Singh - doctoral student, Department of Community Medicine and School of Public Health.

Sector 12, Madhya Marg, Chandigarh, 160012, India

J. S. Thakur

India

Jarnail Singh Thakur - Professor, Department of Community Medicine and School of Public Health.

Sector 12, Madhya Marg, Chandigarh, 160012, India

Supplementary files

Review

Журнал "Сеченовский вестник". Лист редактора можно посмотреть здесь /

Sechenov Medical Journal. Editor's checklist you can find here

Название / Title | Рандомизированное контролируемое исследование в параллельных группах по достижению ремиссии у пациентов с сахарным диабетом 2-го типа через диетические и поведенческие вмешательства: протокол исследования / A parallel arm randomised controlled trial to achieve remission in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus through dietary and behavioural interventions: a study protocol |

Раздел / Section

| ВНУТРЕННИЕ БОЛЕЗНИ / INTERNAL MEDICINE |

Тип / Article | Оригинальная статья / Original article |

Номер / Number | 1097 |

Страна/территория / Country/Territory of origin | Индия / India |

Язык / Language | Английский / English |

Источник / Manuscript source | Инициативная рукопись / Unsolicited manuscript |

Дата поступления / Received | 17.09.2024 |

Тип рецензирования / Type ofpeer-review | Двойное слепое / Double blind |

Язык рецензирования / Peer-review language | Английский / English |

РЕЦЕНЗЕНТ А / REVIEWER A

Инициалы / Initials | 1097_А |

Научная степень / Scientific degree |

|

Страна/территория / Country/Territory | Россия / Russia |

Дата рецензирования / Date of peer-review | 22.12.2024 |

Число раундов рецензирования / Number of peer-review rounds | 2 |

Финальное решение / Final decision | принять к публикации после небольшой доработки/ minor revision |

ПЕРВЫЙ РАУНД РЕЦЕНЗИРОВАНИЯ / FIRST ROUND OF PEER-REVIEW

Scientific quality: Grade C (Fair)

Language quality: Grade B (Minor language polishing)

Re-review: Yes

The problem of achieving remission of type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) is undoubtedly important. The authors describe a multifaceted study to evaluate the efficacy of a lifestyle intervention in achieving remission of type 2 DM compared with a standard intervention. To increase adherence, participants will be supported by group therapy, weekly supervision by a mentor, and a "family leader" will be selected to be responsible for the participant's dietary adherence. Adherence to the recommendations will be monitored regularly using special questionnaires.

However, several questions require clarification.

1) Please provide a more detailed rationale for choosing a low-carbohydrate diet. What percentage of slow-digesting carbohydrates will be recommended to participants? Will consumption of plant fiber be recommended?

The article emphasizes the inclusion of millet in the diet, but it is unclear in what form this product will be presented.

The section on millet in the introduction needs to be expanded. Why was this particular grain chosen? What are its advantages over rice and wheat (low glycemic index, etc.)? Will millet completely replace other grains in the participants' diet? Recent literature on this topic is available online.

The article states that the millet food basket is provided as part of a nutritional support program for tuberculosis patients. It is not clear to the overseas reader how this can be realized if the study participants do not have tuberculosis.

2) IDF and WHO recommend aerobic exercise for people with 2 DM. The article mentions yoga classes, but yoga cannot be considered a full aerobic exercise. Obviously, yoga was chosen because of the Indian culture, but aerobic exercise should be part of the program. This nuance needs clarification.

3) Will participants in the main group receive standard DM therapy as in the control group?

4) Explain why a follow-up period of 9 months is desirable. For example, in studies of DM remission after bariatric surgery, a follow-up period of at least 1 year is usually used. In the planned study, slower weight loss and thus later achievement of remission would be expected. In this context, 9 months of follow-up may not be sufficient.

5) Will the investigator visit weekly for the entire 9 months or only at the beginning?

6) Readers would like to know more about what constitutes a "family champion"? What is the principle behind the selection of this family figure?

7) The difference between the primary purpose of the study (b) and the secondary purpose of the study (c) is not clear:

“To see acceptability among the patients to adopt dietary interventions to achieve remission” vs “To see the user acceptability for dietary and behavior intervention in achieving remission”.

8) One of the main objectives of the study is to assess DM remission in patients in the two groups. However, there is no mention of the planned measurement of glycated hemoglobin levels, evaluation of glycemic diaries.

9) Will the rate of weight loss and reduction in waist circumference be assessed? This is an important aspect of achieving remission of DM.

10) Information on the source of funding for the study should be provided. Promotion of healthy lifestyle principles, lifestyle correction under continuous supervision of a specialist requires a lot of human, material and time resources.

11) Information about research (questionnaires, surveys, etc.) should be placed in a separate subsection. Currently, this information is located in the "Recruitment of Participants" section.

12) An approximate daily diet of a patient and an example of a compliance chart could be provided as illustrative material. The captions in Figure 1 are illegible.

RECOMMENDATION: major revision.

ВТОРОЙ РАУНД РЕЦЕНЗИРОВАНИЯ /SECOND ROUND OF PEER-REVIEW

The authors made many edits and answered almost all key questions. However, some questions remained unanswered.

Key shortcomings:

- No information on the source of funding has been entered.

- The edits and explanations about millet, etc. do not contain references to literature sources, although normative documents are mentioned (again without references). In addition, the explanations are in the format of a dialogue with the reviewer (formulations of ‘Why...?’ and ‘How it works’ and answers to them) and stylistically are not quite appropriate for a scientific article.

Secondary issues and technical comments:

- It is not explained what the nutritional support program for TB patients is and how it relates to diabetic patients.

- The sub-section ‘Recruitment of participants’ still includes information that should have been separated into the ‘Methods’ sub-section. There should be a clearer list of the investigations that are planned at each follow-up visit (HbA1c, weighing, waist circumference measurement, questionnaire analysis...), as in the current version of the text they are scattered in different sections.

- Information on ethical review is duplicated twice (before and after the figure with the study design).

РЕЦЕНЗЕНТ B / REVIEWER B

Инициалы / Initials | 1097_В |

Научная степень / Scientific degree | Доктор медицинских наук / Dr. of Sci. (Medicine) |

Страна/территория / Country/Territory | Россия / Russia |

Дата рецензирования / Date of peer-review | 10.12.2024 |

Число раундов рецензирования / Number of peer-review rounds | 2 |

Финальное решение / Final decision | принять к публикации после небольшой доработки/ minor revision |

ПЕРВЫЙ РАУНД РЕЦЕНЗИРОВАНИЯ / FIRST ROUND OF PEER-REVIEW

Scientific quality: Grade C (Fair)

Language quality: Grade B (Minor language polishing)

Re-review: Yes

General comments:

- Introduction:

Please justify the use of diet and exercise in the treatment of a specific group of patients with T2DM. Please use PICO.

- Methods:

- Please describe the intervention: how it works, how diet and physical activity are selected for patients?

- Please describe the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study.

- Please describe what is included in the standard therapy that patients receive?

- Please specify: primary and secondary (objectives pretty the same) outcomes – how the remission is defined?

- Please define acceptability in detail.

- Do you plan to explore heterogeneity?

- Statistical analysis: describe what methods do you plane to use?

Publication is possible after major revision of the protocol text.

RECOMMENDATION: major revision.

ВТОРОЙ РАУНД РЕЦЕНЗИРОВАНИЯ /SECOND ROUND OF PEER-REVIEW

Thanks to the authors for addressing my comments. The text now reads much more clearly. Interventions and activities to improve patient adherence are explained promptly. Authors need to focus their attention on the target condition in the introduction and rationale. The protocol can be published after minimal revision.