Scroll to:

Primary abdominal pregnancy with a viable fetus: clinical case of successful management

https://doi.org/10.47093/2218-7332.2024.15.3.58-64

Abstract

Abdominal pregnancy, occurring outside typical intrauterine locations, poses substantial risks to maternal health due to the potential for severe bleeding from placental detachment. Despite its rarity, accounting for 1–1.5% of ectopic pregnancies, its mortality rates are significantly higher, with maternal mortality ranging from 2% to 30%.

Case report. A 42-year-old woman, pregnant with her third pregnancy at 33 weeks, was admitted to the hospital with abdominal pain. All antenatal visits were performed without the use of ultrasound. Utilizing ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), we diagnosed an abdominal pregnancy, revealing an extrauterine fetus and placenta, and clarified the location of the placenta, and the involvement of nearby structures. Prompt surgical intervention via laparotomy ensured successful delivery and maternal well-being. The male baby was born in good condition, and no congenital abnormalities were observed.

Discussion: Ultrasound remains the primary diagnostic tool, complemented by MRI for precise evaluation. Early diagnosis is paramount, emphasizing the need for improved clinical understanding and vigilance, with MRI serving as a valuable adjunct in uncertain cases. Early surgical intervention, guided by diagnostic imaging, improves outcomes, underscoring the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to the management of abdominal pregnancy.

Keywords

List of abbreviation

- MRI – magnetic resonance imaging

Pregnancy that arises in the peritoneal cavity outside of the typical tubal, ovarian, or wide ligament regions is referred to as abdominal pregnancy. The mesosalpinx, omentum, and pouch of Douglas are the most often occurring sites. On the other hand, there have been documented cases of implantation in the appendix, liver, and spleen in the abdomen. This rare syndrome is thought to account for 1–1.5 percent of all ectopic pregnancies, or 1 in 8000–10,000 pregnancies [1][2].

The possibility of major bleeding from a partially or fully separated placenta during any trimester of pregnancy poses a serious risk to the mother’s health and may even be fatal. When compared to other types of ectopic pregnancies and even pregnancies inside the uterus, the maternal death risk associated with abdominal pregnancies is significantly higher. Maternal death rates vary globally from 2% to 30%, whereas perinatal death in cases that remain undiagnosed ranges greatly from 40% to 95% [3].

Primary and secondary forms of abdominal pregnancies can be distinguished, with secondary cases being more common. Studdiford’s criteria, which include the absence of a utero-peritoneal fistula, normal bilateral fallopian tubes and ovaries, and an exclusive pregnancy related to the peritoneal surface that occurs early enough to exclude secondary implantation following initial tubal location, are used to define primary abdominal pregnancies. Pregnancies that start in the ovaries or fallopian tubes and then re-implant in the peritoneum, where the embryo or fetus continues to develop, are referred to as secondary abdominal pregnancies [4–6].

We describe a case of a confirmed abdominal pregnancy that was initially misdiagnosed. Maintaining a high level of clinical suspicion is essential for ensuring timely diagnosis and effective management of this condition.

CASE REPORT

A 42-year-old woman, experiencing her third pregnancy, presented to Arifin Achmad Hospital in Pekanbaru at 33 weeks of gestation. She reported abdominal pain that had persisted for two months. Her two previous pregnancies had been uncomplicated. During this pregnancy, she had attended three antenatal care visits at 4, 6, and 7 months, all conducted by a midwife without the use of ultrasound.

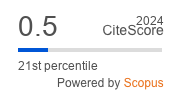

On physical examination, the fetus was palpable through the abdomen. A transabdominal ultrasound revealed that the uterus was anteflexed, measuring 10.49×7.43×6.63 centimeters with an endometrial thickness of 4.06 millimeters (fig. 1A, 1B). Notably, the fetus appeared to be separate from the uterus. The fetal heart rate was recorded at 142 beats per minute, with an estimated fetal weight of 1656 grams. There was no visible uterine wall between the fetus and the urinary bladder, and the fetus was situated very close to the abdominal wall. Visualization of the extrauterine placenta strongly suggested an abdominal pregnancy, a diagnosis that had previously been missed due to the lack of previous ultrasound studies.

FIG. 1. Transabdominal ultrasound examination of a 42-year-old woman with an abdominal pregnancy (A, B).

Note: Vu – vesica urinary; BPD – Biparietal Diameter; HC – Head Circumference.

РИС. 1. Трансабдоминальное ультразвуковое исследование женщины 42 лет с брюшной беременностью (A, B).

Примечание: Vu – vesica urinary, мочевой пузырь; BPD – Biparietal Diameter, бипариетальный диаметр; HC – Head Circumference, окружность головы.

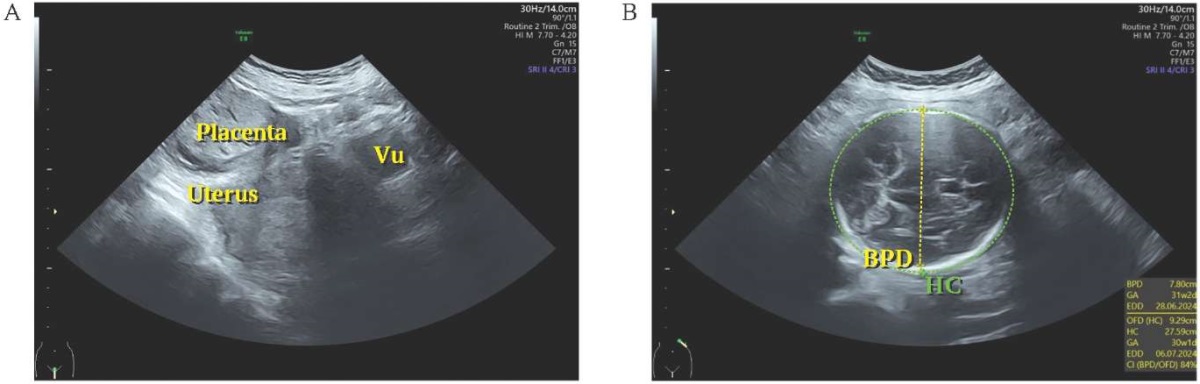

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was then performed to confirm the diagnosis. The MRI results showed an intra-abdominal extrauterine fetus in a transverse position (fig. 2). The placenta was located in the left lower abdomen and was attached to the uterine fundus. The mesentery and distal ileum were in the left abdomen, and the left internal iliac artery, left ovarian vein, and left psoas muscle were involved. The placental feeding artery originated from the left uterine artery, and oligohydramnios was noted.

FIG. 2. The magnetic resonance T2-weighted imaging of a 42-year-old woman with an abdominal pregnancy: the extrauterine fetus is in a transverse position (A – Frontal, B – Axial).

РИС. 2. T2-взвешенные изображения магнитно-резонансной томографии женщины 42 лет с брюшной беременностью: внематочный плод в поперечном положении (А – фронтальная проекция, В – аксиальная проекция).

The preoperative diagnosis was primary abdominal pregnancy without intrauterine pregnancy: O00.0 as classified by the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). A laparotomy was planned with surgical backup.

Surgical technique

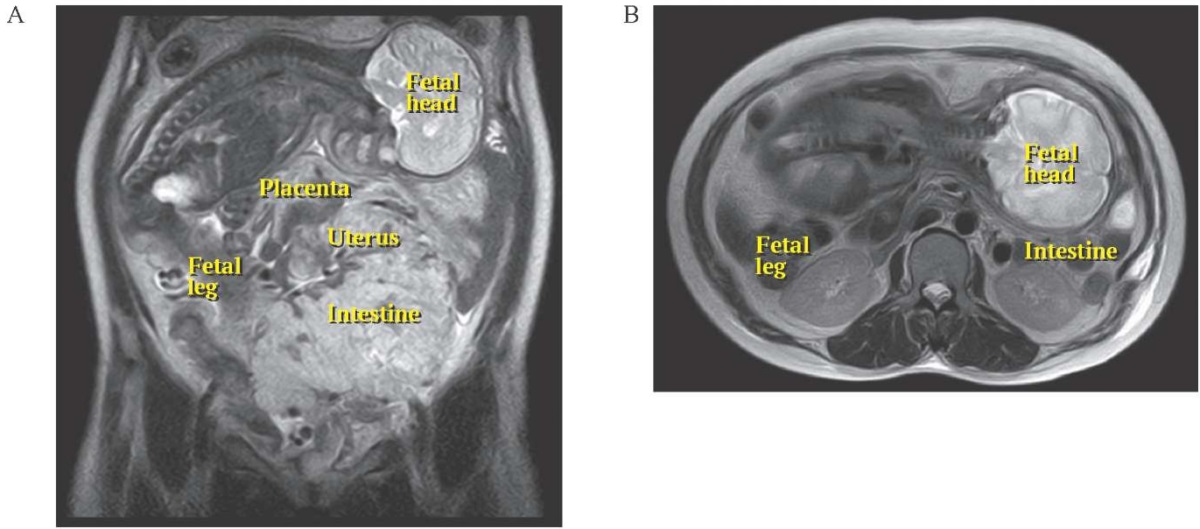

During the operation, which lasted 90 minutes, a vertical incision was made along the midline. Upon opening the peritoneum, parts of the fetus’ arms were visible (fig. 3A). By gently pulling the legs, a male baby was delivered, weighing 1800 grams and height 42 centimetres, with Apgar scores of 4 and 8 (fig. 3B). The baby was born in good condition, cried immediately after birth, and no congenital abnormalities were observed. The umbilical cord was clamped, and an abdominal exploration was performed.

FIG. 3. Laparotomy of a 42-year-old woman with abdominal pregnancy (A. After opening the peritoneum, you can immediately see the fetus hand, B. Photo of the baby shortly after birth, C. Placenta after being removed from the uterus).

РИС. 3. Лапаротомия женщины 42 лет с брюшной беременностью (A. После вскрытия брюшины сразу можно увидеть ручку плода, B. Фотография ребенка вскоре после рождения, C. Плацента после извлечения из матки).

The intestines were protected with a large gauze pad. During the exploration, it was found that the placenta had implanted in the left ovary and extended into the sigmoid colon, necessitating an intraoperative consultation with a surgeon, the technique of separating the placenta from the organs involved by peeling it off little by little with the fingertips if there are difficult parts with the tips of the scissors and there was no intervention in the sigmoid colon or the left psoas muscle. Haemostasis was successfully achieved, and a tubectomy was performed on the right fallopian tube. The exploration revealed that the placenta was located in the left lower abdomen, attached to the uterine fundus (fig. 3С). The mesentery and distal ileum were also situated in the left abdomen. Additionally, the left internal iliac artery, left ovarian vein, and left psoas muscle were involved. The placental feeding artery originated from the left uterine artery and was accompanied by oligohydramnios. The estimated blood loss during the surgery was 1000 mL and during surgery the patient received 240 milliliters of packed red blood cells.

During the hospital stay, the patient’s condition remained stable, and she received 480 millilitres of packed red blood cells. Her postoperative haemoglobin level was 9.3 g/dL. The patient was discharged after three days of treatment. The baby was admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit and was placed on continuous positive airway pressure therapy.

DISCUSSION

Advanced abdominal ectopic pregnancy is very rare and is usually associated with complications that lead to premature termination of pregnancy [7]. In the presented case, the patient carried her pregnancy to 33 weeks and was taken to the hospital due to abdominal pain.

Severe lower abdomen pain is a common symptom, however it might vary. The risk factors for abdominal pregnancy are similar to those for tubal pregnancy. These increase the likelihood of an ectopic pregnancy. They include recent usage of intrauterine contraception and progesterone-only pills, as well as a history of pelvic surgery, pelvic inflammatory disease, sexually transmitted diseases, and allergies [7][8]. This particular patient did not use contraception, did not report other risk factors, and did not have symptoms such as abnormal vaginal discharge. However, she was 42 years old at the time of this pregnancy. Maternal age of 35 years or older is linked to a four- to eight-fold increase in the risk of ectopic pregnancy [8][9].

Diagnosis can often be missed in resource-limited settings due to poor provision of prenatal care, low socioeconomic status of the patient, and lack of adequate medical resources [5][10]. During this pregnancy, the patient had three prenatal care visits without the use of ultrasound, which resulted in a missed diagnosis of an abdominal pregnancy.

Ultrasound, especially transvaginal ultrasound, is still the main method of detecting abdominal pregnancy. Expertise, careful consideration, clinical correlation, and a strong suspicion are crucial for handling clinical uncertainty and ambiguous outcomes. In one case, abdominal pregnancy was detected through transabdominal ultrasonography [11]. Abdominal pregnancy may be diagnosed incidentally on first-trimester sonography or after a patient presents with abdominal pain or bleeding [12].

In our patient, transabdominal ultrasound showed clear signs of abdominal pregnancy: the placenta was located ectopically, the fetus was separated from the uterus and located very close to the abdominal wall. When an accurate diagnosis is required, or when it is unclear how far placental tissue has invaded the abdominal and pelvic organs, MRI can provide additional insight. When necessary, its use is allowed [13]. We used MRI to confirm the diagnosis and clarify the location of the placenta, the vessels that supply it and involvement of nearby structures.

Nontubal ectopic pregnancy has been reported to have a 7 – 8 times higher risk of maternal complications that include spontaneous separation of the placenta leading to massive haemorrhage, shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, organ failure, and death [14]. After diagnosis, treating an abdominal pregnancy usually requires an open laparotomy to provide access for managing bleeding and resolving placental adhesions. On the other hand, because there is little chance of vascularization, removing placental tissue in the early stages of pregnancy is really simple. However, placental extraction becomes more difficult in the third trimester [15][16]. Therefore, we used an interdisciplinary approach. The placenta was implanted into the left ovary and extended into the sigmoid colon and left psoas muscle, requiring intraoperative surgical consultation, which avoided serious complications.

A recently published review of abdominal pregnancy included 113 cases from 2007 to 2019 [14]. Implantation in the bowel and mesenteries was described only in 9 cases, 4 of which required bowel resection [14].

Abdominal pregnancy may be complicated by congenital malformations [5]. The baby was born in good condition, no congenital pathologies were observed.

CONCLUSION

Failure to recognise abdominal pregnancies may have serious repercussions. Gynaecologists need to keep an open mind and develop their ability to comprehend and interpret imaging and clinical results. Ultrasound is often the preferred method of diagnosis in certain cases of abdominal pregnancy. However, inexperienced ultrasound users or those who don’t pay close attention to details can miss the diagnosis. When in doubt, MRI can be used with confidence. When a diagnosis is uncertain, early surgical intervention including minimally invasive methods, can be very helpful.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Donel S. developed the main concept of the article, wrote the text, and agreed to take responsibility for all aspects of the case report. Munawar Adhar Lubis and Citra Utami Effendy participated in the development of the concept of the article and in the preparation of the text. All authors approved the final version of the article.

ВКЛАД АВТОРОВ

Донел С. разработал основную концепцию статьи, написал текст и согласился взять на себя ответственность за все аспекты отчета о случае. Мунавар Адхар Лубис и Ситра Утами Эффенди участвовали в разработке концепции статьи и подготовке текста. Все авторы одобрили окончательную версию статьи.

Compliance with ethical standards. Consent statement. The patient consented to the publication of the article “Primary аbdominal pregnancy with a viable fetus: clinical case of successful management” in the “Sechenov Medical Journal”.

Conflict of interests. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Financial support. The study was not sponsored (own resources).

Соблюдение этических норм. Заявление о согласии. Пациентка дала согласие на публикацию представленной выше статьи «Первичная брюшная беременность с жизнеспособным плодом: клинический случай успешного ведения» в журнале «Сеченовский вестник».

Конфликт интересов. Авторы заявляют об отсутствии конфликта интересов.

Финансирование. Исследование не имело спонсорской поддержки (собственные ресурсы).

References

1. Legesse T.K., Ayana B.A., Issa S.A. Surviving fetus from a full term abdominal pregnancy. Int Med Case Rep J. 2023 Mar 15; 16: 173–178. https://doi.org/10.2147/IMCRJ.S403180. PMID: 36950324

2. Shurie S., Ogot J., Poli P., Were E. Diagnosis of abdominal pregnancy still a challenge in low resource settings: a case report on advanced abdominal pregnancy at a tertiary facility in Western Kenya. Pan Afr Med J. 2018 Dec 20; 31: 239. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2018.31.239.17766. PMID: 31447996

3. Paluku J.L., Kalole B.K., Furaha C.M., et al. Late abdominal pregnancy in a post-conflict context: case of a mistaken acute abdomen – a case report. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Apr 22; 20(1): 238. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-02939-3. PMID: 32321457

4. Aref Hamam Y., Zimmo M., Alqeeq B.F., et al. Advanced secondary abdominal ectopic pregnancy with live fetus at 26-weeks’ gestation following in vitro fertilization: A case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2024 Jan 30; 12: 2050313X241226776. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050313X241226776. PMID: 38292876

5. Mulisya O., Barasima G., Lugobe H.M., et al. Abdominal pregnancy with a live newborn in a low-resource setting: A case report. Case Rep Womens Health. 2023 Jan 11; 37:e 00480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crwh.2023.e00480. PMID: 36683781

6. George R., Powers E., Gunby R., et al. Abdominal ectopic pregnancy. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2021 Mar 5; 34(4): 530–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/08998280.2021.1884932. PMID: 34219949

7. Byamukama A., Bibangambah P., Rwebazibwa J. Advanced abdominal ectopic pregnancy and the role of antenatal ultrasound scan in its diagnosis and management. Radiol Case Rep. 2023 Oct 6; 18(12): 4409–4413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radcr.2023.09.042. PMID: 37840888

8. Fessehaye A., Gashawbeza B., Daba M., et al. Abdominal ectopic pregnancy complicated with a large bowel injury: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2021 Mar 22; 15(1): 127. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-021-02713-9. PMID: 33745446; PMCID: PMC7983259

9. Cosentino F., Rossitto C., Turco L.C., et al. Laparoscopic management of abdominal pregnancy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017 Jul-Aug; 24(5): 724–725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2017.01.023. Epub 2017 Feb 4. PMID: 28179200

10. Zhang Y., Li M., Liu X., et al. A delayed spontaneous second-trimester tubo-abdominal pregnancy diagnosed and managed by laparotomy in a “self-identified” infertile woman, a case report and literature review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023 Jul 13; 23(1): 511. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05793-1. PMID: 37442982

11. Pak J.O., Durfee J.K., Pedro L., et al. Retroperitoneal ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Dec; 132(6): 1491–1493. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002965. PMID: 30399096

12. Mamo A., Adkins K. Abdominal pregnancy: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Gynecol Surg. 2022; 38 (3): 193–196. https://doi.org/10.1089/gyn.2022.0013

13. OuYang Z., Wei S., Wu J., et al. Retroperitoneal ectopic pregnancy: A literature review of reported cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021 Apr; 259: 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.02.014. Epub 2021 Feb 18. PMID: 33640664

14. Eisner S.M., Ebert A.D., David M. Rare ectopic pregnancies – A literature review for the period 2007 - 2019 on locations outside the uterus and fallopian tubes. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2020 Jul; 80(7): 686–701. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1181-8641. Epub 2020 Jul 14. PMID: 32675831

15. ELmiski F., Ouafidi B., Elazzouzi E., et al. Abdominal pregnancy diagnosed by ultrasonography and treated successfully by laparotomy: Two cases report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2021 Jun; 83: 105952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2021.105952. Epub 2021 Apr 30. PMID: 34020404; PMCID: PMC8142248

16. Tegene D., Nesha S., Gizaw B., et al. Laparotomy for advanced abdominal ectopic pregnancy. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2022 Mar 8; 2022: 3177810. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3177810. PMID: 35299756

About the Authors

S. DonelIndonesia

PhD, MD, Associate Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Fetomaternal Division, Faculty of Medicine, University of Riau; Arifin Achmad General Hospital.

Kampus Bina Widya KM. 12,5, Simpang Baru, Kec. Tampan, Kota Pekanbaru, Riau 28293

Munawar Adhar Lubis

Indonesia

MD, Student, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Riau; Arifin Achmad General Hospital.

Kampus Bina Widya KM. 12,5, Simpang Baru, Kec. Tampan, Kota Pekanbaru, Riau 28293

Citra Utami Effendy

Indonesia

MD, Student, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Riau; Arifin Achmad General Hospital.

Kampus Bina Widya KM. 12,5, Simpang Baru, Kec. Tampan, Kota Pekanbaru, Riau 28293

Supplementary files

|

1. CARE Checklist | |

| Subject | ||

| Type | Исследовательские инструменты | |

Download

(502KB)

|

Indexing metadata ▾ | |