Scroll to:

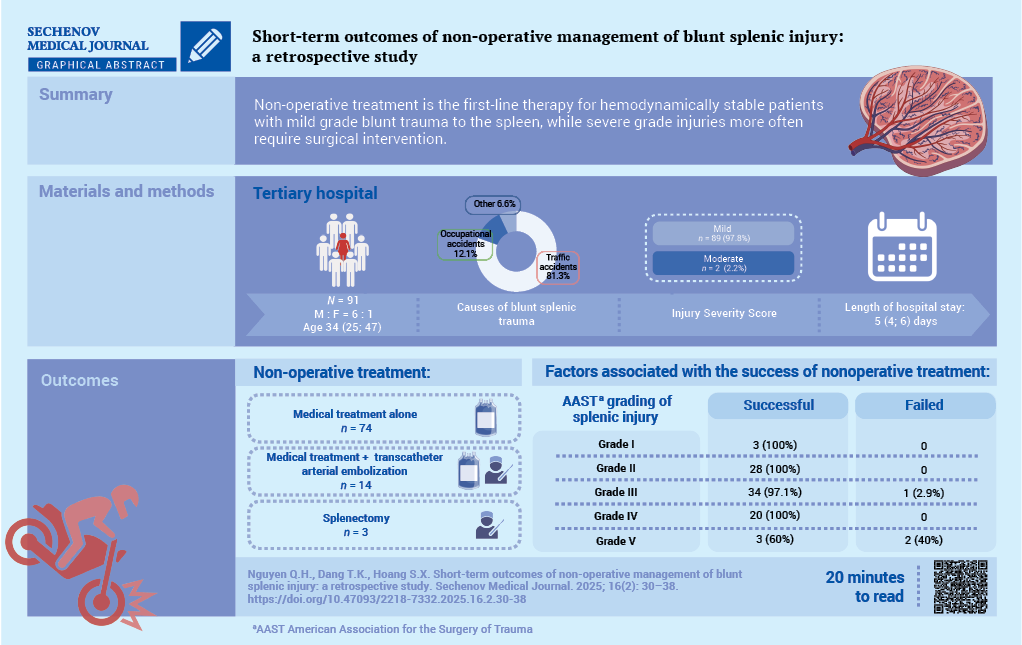

Short-term outcomes of non-operative management of blunt splenic injury: a retrospective study

https://doi.org/10.47093/2218-7332.2025.16.2.30-38

Abstract

Aim. To evaluate the short-term outcomes of non-operative management (NOM) for blunt splenic trauma and to identify prognostic factors for its success at a tertiary hospital.

Methods. The study cohort comprised 136 patients with blunt splenic rupture treated at People’s Hospital 115, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, between January 2021 and December 2023. Non-operative management was implemented in 91 cases (66.9%). Collected data included demographics, injury characteristics, therapeutic interventions, complications and NOM outcomes.

Results. Among the 91 patients who received NOM, the median age was 34 (25; 47) years with male-to-female ratio of 6:1. Traffic accidents accounted for most splenic ruptures (81.3%). Clinical symptoms included abdominal pain (98.9%) and distension (27.5%). Abdominal computed tomography findings according to the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) classification revealed predominantly Grade II (30.8%) and Grade III (38.5%) splenic injuries. The hemoperitoneum volume correlated significantly with injury severity (p = 0.029). NOM was successful in 88 patients (96.7%), whereas three patients (3.3%) required splenectomy. The median hospital stay was 5 (4; 6) days. The median amount of blood transfusion was 937.5 ± 340.9 ml. No mortality was reported

Conclusions. Our findings confirm that NOM should be considered as a first-line therapy for hemodynamically stable patients with blunt splenic injury, as it safely obviates the need for surgery while avoiding operation-associated morbidity.

Keywords

Abbreviations:

- AAST – American Association for the Surgery of Trauma

- ASA – American Society of Anesthesiologists

- CT – computed tomography

- DSA – digital subtraction angiography

- NOM – non-operative management

- TAE – transcatheter arterial embolization

The spleen is one of the most frequently vulnerable organs, accounting for about 32% of patients with blunt abdominal trauma [1][2]. This injury can lead to severe internal bleeding and hemorrhagic shock with a mortality rate of 7–18% if diagnosis and treatment are delayed [3]. Motor vehicle accidents and falls are the most prevalent causes of splenic injury in blunt abdominal trauma [1][4].

Treatment modalities for blunt splenic injury include surgical interventions (splenorrhaphy and splenectomy) and non-operative management (NOM). Laparotomy is a recommended therapeutic option for blunt splenic injury and splenectomy is often unavoidable in hemodynamically unstable patients [1][5][6]. However, the spleen plays a critical role in the immune defense response, including filtration, blood storage and phagocytosis [3]. Therefore, organ-preserving strategies were proposed with initial studies focusing on pediatric cases [6].

Over the past few decades, because of advances in modern diagnostic tools and medical interventions, the management of splenic trauma has shifted significantly in favor of NOM. For hemodynamically stable patients, NOM may require close monitoring with or without digital subtraction angiography (DSA) or DSA with selective splenic embolization [1][3][6].

The aim of the study is to evaluate the short-term outcomes of NOM for blunt splenic trauma and to identify prognostic factors for its success at a tertiary hospital.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

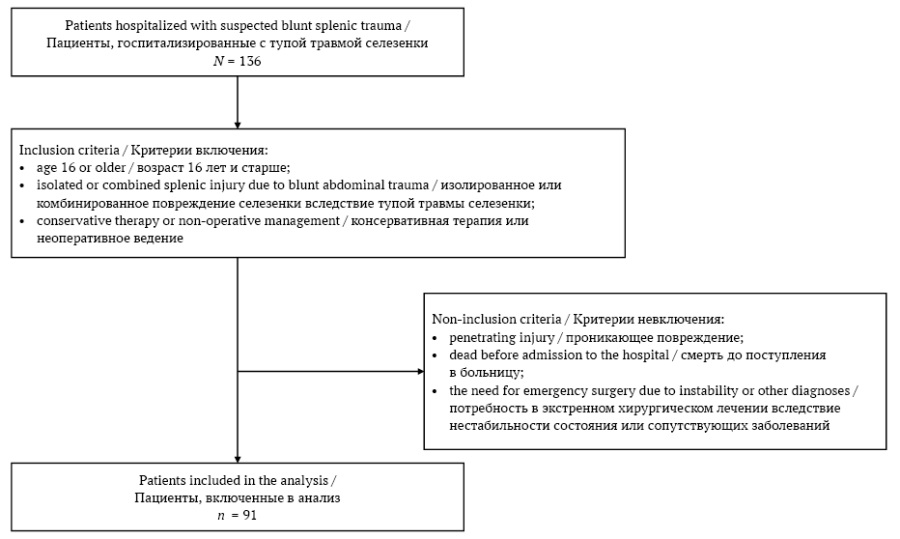

The retrospective study included patients admitted to People’s Hospital 115 (a tertiary hospital) with a diagnosis of blunt splenic injury according to the classification codes of the International Classification of Disease 10th revision (ICD-10) between January 2021 and December 2023.

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

- age 16 or older;

- isolated or combined splenic injury due to blunt abdominal trauma;

- conservative therapy or NOM.

Non-inclusion criteria were:

- penetrating injury;

- death before admission to the hospital;

- the need for emergency surgery due to instability or other diagnoses.

Data were collected on demographics, clinical symptoms, trauma causes, radiological injury characteristics, and medical interventions.

The study flowchart is illustrated in Figure. A total of 136 patients with blunt splenic injury were assessed, of whom 91 (66.9%) were included in the study.

FIG. The study flowchart

РИС. Потоковая диаграмма исследования

All patients admitted for blunt splenic trauma were managed according to the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS®) guidelines by the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (Chicago, USA) [7]. Fluid resuscitation and blood replacement were administered to maintain hemodynamic stable.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was performed to assess the grade of splenic injury, the extent of haemoperitoneum, presence of peritonitis and other associated injuries. If active splenic arterial bleeding or a pseudoaneurysm was identified using CT, transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) was performed by interventional radiologists.

When DSA of the celiac artery and splenic artery identified the bleeding site, superselective embolization was performed using embolic materials such as gelatin sponge, Lipiodol, Histoacryl or fibered coil (Boston Scientific, USA).

The primary endpoint was the success of NOM during the current hospitalization.

Statistical data analysis

Data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Categorical variables are presented as frequencies (%), continuous variables as mean values ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) depending on the distribution. For categorical variables, the chi-square test was used. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., USA).

RESULTS

The median age was 34 (25; 47) years, and the male-to-female ratio was 6:1. Traffic accidents were the leading cause (81.3%), followed by occupational accidents (12.1%). Moreover, 73.6% of patients arrived within 12 hours of trauma. Also, 50 patients (54.9%) received first aid at the healthcare facilities, and 41 patients (45.1%) did not receive first aid or went to the hospital directly. The clinical symptoms, laboratory tests, and diagnostic imaging results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. The baseline characteristics of patients with blunt splenic trauma

Таблица 1. Исходные характеристики пациентов с тупой травмой селезенки

|

Variables / Параметры |

No. of patients / Количество пациентов (n = 91) |

% |

|

Sex / Пол |

||

|

male / муж |

78 |

85.7 |

|

female / жен |

13 |

14.3 |

|

Clinical symptoms / Клинические симптомы |

||

|

splenic pain / боль в области селезенки |

83 |

91.2 |

|

peritoneal reaction / симптомы раздражения брюшины |

4 |

4.4 |

|

abdominal distention / вздутие живота |

25 |

27.5 |

|

Anemia / Анемия |

||

|

none (Hb > 12 g/dl) / нет (Hb > 12 г/дл) |

54 |

59.3 |

|

mild (Hb = 10–12 g/dl) / легкая (Hb = 10–12 г/дл) |

27 |

29.7 |

|

moderate (Hb = 8–10 g/dl) / умеренная (Hb = 8–10 г/дл) |

7 |

7.7 |

|

severe (Hb < 8 g/dl) / тяжелая (Hb < 8 г/дл) |

3 |

3.3 |

|

The amount of hemoperitoneum on computed tomography findings / Объем гемоперитонеума по данным компьютерной томографии |

||

|

none / отсутствует |

10 |

11.0 |

|

mild / минимальный |

43 |

47.2 |

|

moderate / умеренный |

30 |

33.0 |

|

severe / выраженный |

8 |

8.8 |

|

AAST grading of splenic injury / Классификация травмы селезенки по AAST |

||

|

grade I / I степень |

3 |

3.3 |

|

grade II / II степень |

28 |

30.8 |

|

grade III / III степень |

35 |

38.5 |

|

grade IV / IV степень |

20 |

22.0 |

|

grade V / V степень |

5 |

5.5 |

|

Associated injuries / Сопутствующие повреждения |

||

|

chest / грудная клетка |

21 |

23.1 |

|

face / лицо |

8 |

8.8 |

|

brain / головной мозг |

2 |

2.2 |

|

bones / костные структуры |

10 |

11.0 |

|

abdomen and visceral pelvis (other than spleen) / брюшная полость и органы малого таза (кроме селезенки) |

11 |

12.1 |

|

liver / печень |

1 |

1.1 |

|

kidneys / почки |

10 |

11.0 |

|

DSA (n = 17) / ЦСА (n = 17) |

||

|

splenic artery pseudoaneurysm / псевдоаневризма селезеночной артерии |

1 |

1.1a |

|

contrast extravasation from the splenic artery / экстравазация контрастного вещества из селезеночной артерии |

15 |

16.5a |

|

no lesion / нет повреждения |

1 |

1.1a |

|

ISS scores / Показатель ISS |

||

|

mild (<9) / легкая степень (<9) |

89 |

97.8 |

|

moderate (9–15) / умеренная степень (9–15) |

2 |

2.2 |

Notes: a The percentage of patients who underwent DSA.

AAST – American Association for the Surgery of Trauma; DSA – digital subtraction angiography; ISS – Injury Severity Score.

Примечания: a Доля от пациентов, которым проведена ЦСА.

AAST – American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (Американская ассоциация хирургии травмы); ISS – Injury Severity Score (шкала тяжести травмы); ЦСА – цифровая субтракционная ангиография.

The severity of the hemoperitoneum correlated with increasing the grade of splenic injury (p = 0.029) (Table 2).

Table 2. Distribution of severity of hemoperitoneum following the grade of splenic injury

Таблица 2. Распределение степени выраженности гемоперитонеума в зависимости от степени повреждения селезенки

|

Hemoperitoneum volume / Объем гемоперитонеума |

AAST grading of splenic injury / Классификация травмы селезенки по AAST |

Total / Всего |

р-value / p-значение |

||||

|

Grade I / |

Grade II / |

Grade III / |

Grade IV / |

Grade V / |

|||

|

None / Нет |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0.029 |

|

Mild (100–200 ml) / Легкий (100–200 мл) |

2 |

10 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

19 |

|

|

Moderate (200–500 ml) / Умеренный (200–500 мл) |

0 |

15 |

24 |

15 |

3 |

57 |

|

|

Large (>500 ml) / Большой (>500 мл) |

1 |

1 |

5 |

4 |

2 |

13 |

|

|

Total / Всего |

3 |

28 |

35 |

20 |

5 |

91 |

|

Note: AAST – American Association for the Surgery of Trauma.

Примечание: AAST – American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (Американская ассоциация хирургии травмы).

The length of hospital stay ranged from 1 to 26 days, with a median of 5 (4; 6) days. The median blood transfusion volume was 937.5 ± 340.9 mL.

Concerning the interim treatment outcomes, 88 patients (96.7%) were stable and discharged from the hospital following NOM. Of these patients, 74 received medical treatment alone while 14 received a combination of medical therapy and TAE. The distribution of successful NOM rates following Grades I–V of blunt splenic injury was 100%, 100%, 97.1%, 100%, and 60%, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. The distribution of successful and failed non-operative management patients following the grade of splenic injury

Таблица 3. Распределение успешных и неудачных случаев неоперативного лечения в зависимости от степени повреждения селезенки

|

AAST grading of splenic injury / Классификация травмы селезенки по AAST |

Successful NOM / Успех НОЛ |

Failed NOM / Неудача НОЛ |

р-value / p-значение |

|

Grade I / I степень, n (%) |

3 (100) |

0 |

0.0001 |

|

Grade II / II степень, n (%) |

28 (100) |

0 |

|

|

Grade III / III степень, n (%) |

34 (97.1) |

1 (2.9) |

|

|

Grade IV / IV степень, n (%) |

20 (100) |

0 |

|

|

Grade V / V степень, n (%) |

3 (60) |

2 (40) |

|

|

Total / Всего |

88 (96.7) |

3 (3.3) |

Note: AAST – American Association for the Surgery of Trauma; NOM – non-operative management.

Примечание: AAST – Американская ассоциация хирургии травмы (American Association for the Surgery of Trauma); НОЛ – неоперативное лечение.

Only three patients experienced persistent intra-abdominal bleeding and hemodynamic instability despite NOM, necessitating urgent open total splenectomy (the characteristics of these cases are summarized in (Table 4). As a result, all three patients achieved postoperative progress and were successfully discharged. There were no mortalities in the study cohort.

Table 4. Characteristics of the admission and postoperative features on patients with non-operative management failure

Таблица 4. Показатели при поступлении и послеоперационные данные у пациентов с неэффективным неоперативным лечением

|

Sex, age / Пол, возраст |

Systolic BP mmHg) / Систолическое АД (мм рт. ст.) |

Hct (%) |

AAST |

ISS |

Hemoperitoneum (mL) / Гемоперитонеум (мл) |

DSA / ЦСА |

Treatment / Лечение |

Fluid transfusion (mL) / Объем инфузионной терапии (мл) |

|

Female, 85a / Женщина, 85a |

70 |

26.5 |

III |

Mild / Легкая |

500–1000 |

Contrast extravasation / Экстравазация КВ |

Medical + angiography / Медикаментозное + ангиография |

2000 |

|

Male, 29 / Мужчина, 29 |

110 |

29.9 |

V |

Mild / Легкая |

1000–1500 |

Contrast extravasation / Экстравазация КВ |

Medical + angiography / Медикаментозное + ангиография |

400 |

|

Male, 21 / Мужчина, 21 |

100 |

37.6 |

V |

Mild / Легкая |

1500–2000 |

Contrast extravasation / Экстравазация КВ |

Medical + angiography / Медикаментозное + ангиография |

3500 |

Notes: a Concomitant Grade III lateral kidney injury.

AAST – American Association for the Surgery of Trauma; BP – Blood pressure; DSA – digital subtraction angiography; Hct – Hematocrit; ISS – Injury Severity Score.

Примечания: a Сопутствующее повреждение боковой поверхности почки III степени.

AAST – American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (Американская ассоциация хирургии травмы); Hct – Hematocrit (гематокрит); ISS – Injury Severity Score (шкала тяжести травмы); АД – артериальное давление; КВ – контрастное вещество; ЦСА – цифровая субтракционная ангиография.

DISCUSSION

In cases of splenic injury due to blunt abdominal trauma, NOM has emerged as the gold standard for hemodynamically stable patients without signs of peritonitis [2][3][5]. B. Garber et al. reported in a multicentric retrospective analysis that NOM became the preferred therapeutic strategy, followed by splenectomy and splenorrhaphy. The rate of NOM increased from 59% in 1991 to 75% in 1994, while splenectomy rates declined from 35% to 24% during the same period [8].

Recent studies indicate that NOM of blunt splenic injury is feasible in 74–88% of cases [9][10]. Among patients with blunt splenic injury in this study, NOM was possible in 66.9%. There is a male predominance in blunt splenic injury (85%), with motor vehicle and motorbike accidents being the primary cause of such injuries. As reported in other studies, the prevalence among men was about 70–80% [6][11][12]. Since the most common vehicle in Vietnam is the motorcycle, motorcycle accidents are the leading cause of blunt abdominal trauma, especially splenic injury [13].

Abdominal ultrasound and contrast-enhanced CT could allow for assessing hemoperitoneum volume, injury severity, and associated abdominal organ damage. In this study, imaging findings revealed splenic injuries predominantly classified as Grades II–III according to AAST scale, accompanied by mild-to-moderate hemoperitoneum. A. Yildiz et al. reported Grades II and III injuries as the most common (34.1% and 35.4%, respectively). The extent of hemoperitoneum correlated positively with the severity of splenic injury [14]. In the present study, NOM of blunt splenic injury demonstrated a high success rate of 96.7%, and in only three patients (3.3%) did it prove not successful. Currently, NOM has become the primary treatment strategy for splenic injuries, with success rates ranging from 80% to 100% [10][15–18]. A. Brillantino et al. reported a comparable failure rate of 4.6% [18].

The severity of the splenic injury is a critical predictor of NOM failure. Previous studies have classified Grade I-III spleen injuries as low grade, whereas Grade IV–V is considered high grade. If Grade III spleen damage is accompanied by concomitant solid organ injury, it may be reclassified as a high-grade. The incidence of NOM failure increased progressively with the increasing grade of splenic injury.

In this study, the Grade I–V spleen injuries were successfully treated with NOM in 100%, 100%, 97.1%, 100%, and 60% (p = 0.0001), respectively. A. Yildiz et al. demonstrated that the success rates in Grade I-V spleen injuries were 100%, 96.3%, 92.8%, 57.7%, and 0% [14]. In three patients with NOM failure, two patients had Grade V splenic injury and one patient had Grade III splenic injury with an older age (85 years). Moreover, this patient had concomitant Grade III lateral kidney injury. All three patients had contrast extravasation on angiography and required more than three units of blood transfusion.

A. Yildiz et al. suggested that the grade of splenic injury, hemoperitoneum volume, the age being over 55 years old, the presence of contrast extravasation or pseudoaneurysm on CT, and requiring a transfusion of more than four units of blood within the first 24 h were considered risk factors for NOM failure. Additionally, other factors including ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) physical status classification, GCS (Glasgow Coma Scale), ISS (Injury Severity Score), and RTS (Revised Trauma Score), comorbidities, and abdominal and extra-abdominal organ injuries, have impacted NOM success [18–21].

NOM failure typically occurs within four days following trauma, with a maximum reported delay of 26 days [11]. A. Peitzman et al. found that 78.9% of failures happened within 48 hours of admission, with the remainder failing between days 7 and 12 [4]. In this study, three cases experienced NOM failure on day 2. CT scanning was frequently performed to monitor hospitalized or discharged patients, but this is controversial. Repeat imaging of low-grade splenic injuries is not necessary unless there is evidence of intra-abdominal hemorrhage. Nonetheless, repeat CT scans in hospitalized patients may detect vascular anomalies such as splenic artery pseudoaneurysms [14].

In the present study, we indicated TAE in patients who had contrast extravasation or artery pseudoaneurysm on CT immediately after admission. In three cases with NOM failure, TAE could enhance the outcomes of blunt splenic injuries and increase the splenic salvage rates. Most studies suggested using TAE only for patients with a contrast hemorrhage or posttraumatic pseudoaneurysm of the splenic artery on CT [11][21].

The limitations of this study are as follows: 1) this is a retrospective study; 2) sample size was limited; 3) this was a single-center study. The failure rate of NOM in the study was low. Therefore, no predictive variables could be provided.

CONCLUSION

Out of all the solid organs, the spleen is one of the most vulnerable to blunt abdominal trauma. NOM is preferred for managing hemodynamically stable patients, demonstrating a relatively high success rate, especially in patients with mild to moderate splenic rupture severity. TAE in combination with medical treatment enhances the rate of splenic salvage.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Quang H. Nguyen and Toan K. Dang conceived and designed the study. They also wrote the article. Song X. Hoang collected and analyzed the data, as well as participated in the drafting of the article. Quang H. Nguyen analyzed and interpreted the data. All of the authors approved the final version of the publication.

ВКЛАД АВТОРОВ

К.Х. Нгуен, Т.К. Данг разработали концепцию и дизайн исследования, написали статью. Ш.С. Хоанг осуществил сбор и анализ данных, участвовал в написании статьи. К.Х. Нгуен проанализировал и интерпретировал данные. Все авторы одобрили окончательную версию публикации.

Ethics statements. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set out in the Helsinki Declaration, version 2024. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by People's Hospital 115’s local ethics committee on 10 October 2024 (approval number 2395/QĐ-BVND115). Obtaining informed consent from patients and their legal representatives was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study and analysis of anonymous clinical data.

Data access. The data that support the findings of this study have been published and available via https://doi.org/10.47093/22187332.2025.16.2.30-38-annex. The data and statistical methods presented in the article have been statistically reviewed by the journal editor, a certified biostatistician.

Conflict of interests. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Financial support. The study was not sponsored (own resources).

Соблюдение этических норм. Данное исследование проведено в соответствии с этическими стандартами Хельсинкской декларации версии 2024 года. Протокол исследования рассмотрен и одобрен 10.10.2024 локальным этическим комитетом Народной больницы 115 (номер одобрения 2395/QĐ-BVND115). Получение информированных согласий пациентов и их законных представителей не требовалось из-за ретроспективного характера исследования и анализа анонимных клинических данных.

Доступ к данным. Данные, подтверждающие выводы этого исследования, опубликованы и доступны по ссылке: https://doi.org/10.47093/2218-7332.2025.16.2.30-38-annex. Данные и статистические методы, представленные в статье, были проверены редактором журнала, сертифицированным биостатистиком.

Конфликт интересов. Авторы заявляют об отсутствии конфликта интересов.

Финансирование. Исследование не имело спонсорской поддержки (собственные ресурсы).

References

1. Corn S., Reyes J., Helmer S.D., Haan J.M. Outcomes following blunt traumatic splenic injury treated with conservative or operative management. Kans J Med. 2019 Aug; 12(3): 83–88. https://doi.org/10.17161/kjm.v12i3.11798. PMID: 31489105

2. Larsen J.W., Thorsen K., Søreide K. Splenic injury from blunt trauma. Br J Surg. 2023; 110(9): 1035–1038. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjs/znad060. PMID: 36916679

3. Meira Júnior J.D., Menegozzo C.A.M., Rocha M.C., Utiyama E.M. Non-operative management of blunt splenic trauma: evolution, results and controversies. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2021; 48: e20202777. https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-6991e-20202777. PMID: 33978122

4. Peitzman A.B., Heil B., Rivera L., et al. Blunt splenic injury in adults: Multi-institutional Study of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma. 2000 Aug; 49(2): 177–187. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-200008000-00002. PMID: 10963527

5. Coccolini F., Montori G., Catena F., et al. Splenic trauma: WSES classification and guidelines for adult and pediatric patients. World J Emerg Surg. 2017 Aug 18; 12: 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-017-0151-4. PMID: 28828034

6. Huang J.F., Kuo L.W., Hsu C.P., et al. Long-term follow-up of infection, malignancy, thromboembolism, and all-cause mortality risks after splenic artery embolization for blunt splenic injury: comparison with splenectomy and conservative management. BJS Open. 2025 Mar 4; 9(2): zraf037. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsopen/zraf037. PMID: 40231931

7. Kortbeek J.B., Al Turki S.A., Ali J., et al. Advanced trauma life support, 8th edition, the evidence for change. J Trauma. 2008 Jun; 64(6): 1638–1650. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e3181744b03. PMID: 18545134

8. Garber B.G., Mmath B.P., Fairfull-Smith R.J., Yelle J.D. Management of adult splenic injuries in Ontario: a population-based study. Can J Surg. 2000 Aug; 43(4): 283–288. PMID: 10948689

9. Fodor M., Primavesi F., Morell-Hofert D., et al. Non-operative management of blunt hepatic and splenic injury: a time-trend and outcome analysis over a period of 17 years. World J Emerg Surg. 2019; 14: 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-019-0249-y. PMID: 31236129

10. Lavanchy J.L., Delafontaine L., Haltmeier T., et al. Increased hospital treatment volume of splenic injury predicts higher rates of successful non-operative management and reduces hospital length of stay: a Swiss Trauma Registry analysis. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2022; 48: 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-020-01582-z. Epub 2021 Jan 23. PMID: 33484278

11. Renzulli P., Gross T., Schnüriger B., et al. Management of blunt injuries to the spleen. Br J Surg. 2010 Nov; 97(11): 1696–1703. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.7203. PMID: 20799294

12. van der Vlies C.H., Hoekstra J., Ponsen K.J., et al. Impact of splenic artery embolization on the success rate of non-operative management for blunt splenic injury. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2012; 35: 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-011-0132-z. Epub 2011 Mar 24. PMID: 21431976

13. Quang V.V., Anh N.H.N. Evaluation of non-operative management of blunt splenic injury at 108 Military Hospital. J 108-Clin Med Pharm. 2021; 16(7): 37–45. https://doi.org/10.52389/ydls.v16i7.894

14. Yıldız A., Özpek A., Topçu A., et al. Blunt splenic trauma: Analysis of predictors and risk factors affecting the non-operative management failure rate. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2022 Oct; 28(10): 1428–1436. https://doi.org/10.14744/tjtes.2022.95476. PMID: 36169475

15. Haan J.M., Bochicchio G.V., Kramer N., Scalea T.M. Nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury: a 5-year experience. J Trauma. 2005; 58: 492–498. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000154575.49388.74. PMID: 15761342

16. Requarth J.A., D’Agostino R.B. Jr, Miller P.R. Non-operative management of adult blunt splenic injury with and without splenic artery embolotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Trauma. 2011; 71: 898–903. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e318227ea50. PMID: 21986737

17. Bhangu A., Nepogodiev D., Lal N., Bowley D.M. Meta-analysis of predictive factors and outcomes for failure of non-operative management of blunt splenic trauma. Injury. 2012; 43: 1337–1346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2011.09.010. Epub 2011 Oct 13. PMID: 21999935

18. Brillantino A., Iacobellis F., Robustelli U., et al. Non operative management of blunt splenic trauma: a prospective evaluation of a standardized treatment protocol. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2016; 42: 593–598. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00068-015-0575-z. Epub 2015 Sep 28. PMID: 26416401

19. Olthof D.C., Joosse P., van der Vlies C.H., et al. Prognostic factors for failure of non-operative management in adults with blunt splenic injury: A systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013; 74: 546–557. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e31827d5e3a. PMID: 23354249

20. Cocanour C.S., Moore F.A., Ware D.N., et al. Delayed complications of non-operative management of blunt adult splenic trauma. Arch Surg. 1998; 133: 619–624; discussion 624–625. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.133.6.619. PMID: 9637460

21. Shelat V.G., Khoon T.E., Tserng T.L., et al. Outcomes of nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury–Asian experience. Int Surg. 2015; 100(9–10): 1281–1286. https://doi.org/10.9738/INTSURG-D-14-00160.1

About the Authors

Q. H. NguyenViet Nam

Quang H. Nguyen, Dr. of Sci. (Medicine), Head of the Department of General Surgery; Lecturer, Department of medicine

527, Su Van Hanh str., Ward 12, District 10, Ho Chi Minh City, 700000

300A, Nguyen Tat Thanh str., Ward 13, District 4, Ho Chi Minh City, 700000

T. K. Dang

Viet Nam

Toan K. Dang, surgeon of the Department of General Surgery

527, Su Van Hanh str., Ward 12, District 10, Ho Chi Minh City, 700000

S. X. Hoang

Viet Nam

Song X. Hoang, surgeon of the Department of General Surgery

527, Su Van Hanh str., Ward 12, District 10, Ho Chi Minh City, 700000

Supplementary files

|

1. Dataset | |

| Subject | ||

| Type | Исследовательские инструменты | |

Download

(19KB)

|

Indexing metadata ▾ | |

|

|

2. Graphic abstract | |

| Subject | ||

| Type | Исследовательские инструменты | |

View

(161KB)

|

Indexing metadata ▾ | |

|

3. STROBE checklist_cohort studies | |

| Subject | ||

| Type | Исследовательские инструменты | |

Download

(141KB)

|

Indexing metadata ▾ | |

Review

Sechenov Medical Journal. Editor's checklist for this article you can find here.

Журнал «Сеченовский вестник» |

| Sechenov Medical Journal |

Рецензии на рукопись |

| Peer-review reports |

Название / Title | Краткосрочные результаты неоперативного лечения тупой травмыселезенки: ретроспективное исследование. / Short-term outcomes of non-operative management of blunt splenic injury: a retrospective study.

|

Раздел / Section

| ХИРУРГИЯ / SURGERY

|

Тип / Article | Оригинальная статья / Original article

|

Номер / Number | 1218

|

Страна/территория / Country/Territory of origin | Вьетнам / Viet Nam |

Язык / Language | Английский / English

|

Источник / Manuscript source | Инициативная рукопись / Unsolicited manuscript |

Дата поступления / Received | 24.04.2025

|

Тип рецензирования / Type ofpeer-review | Двойное слепое / Double blind |

Язык рецензирования / Peer-review language | Английский / English |

РЕЦЕНЗЕНТ А / REVIEWER A

Инициалы / Initials | 1218_А

|

Научная степень / Scientific degree | Кандидат медицинских наук / Cand. of Sci. (Medicine)

|

Страна/территория / Country/Territory | Россия / Russia

|

Дата рецензирования / Date of peer-review | 16.06.2025

|

Число раундов рецензирования / Number of peer-review rounds | 2 |

Финальное решение / Final decision | принять к публикации / accept

|

ПЕРВЫЙ РАУНД РЕЦЕНЗИРОВАНИЯ / FIRST ROUND OF PEER-REVIEW

Scientific quality: Grade C (Fair)

Language quality: Grade B (Minor language polishing)

Re-review: Yes

For a higher level of validity of the conclusions, well-planned cohort studies, ideally randomized, are required. Non-operative management of hemodynamically stable or stabilized patients with blunt trauma of the parenchymal organs of the abdomen is

increasingly being introduced into daily practice. There are studies on the treatment of hemodynamically unstable patients, including those with penetrating abdominal wounds. The correct choice of patients for non-operative management will help to improve the treatment outcomes of patients with abdominal trauma.

In Table 3 the level of statistical significance of p is indicated in the singular, it is not entirely clear which groups it shows the difference between. It would be good to indicate the level of statistical significance of p in the groups depending on the volume of the hemoperitoneum and the severity of the organ injury.

You can also enter a p-level in Table 2 to show the statistical significance of the differences in the effective and ineffective groups of non-operative management.

Recommendation after the first round of peer-review: minor revision.

ВТОРОЙ РАУНД РЕЦЕНЗИРОВАНИЯ /SECOND ROUND OF PEER-REVIEW

All comments have been addressed by authors.

РЕЦЕНЗЕНТ B / REVIEWER B

Инициалы / Initials | 1218_В

|

Научная степень / Scientific degree | Кандидат медицинских наук / Cand. of Sci. (Medicine)

|

Страна/территория / Country/Territory | Россия / Russia

|

Дата рецензирования / Date of peer-review | 13.06.2025

|

Число раундов рецензирования / Number of peer-review rounds | 2 |

Финальное решение / Final decision | Принять к публикации / Accept

|

ПЕРВЫЙ РАУНД РЕЦЕНЗИРОВАНИЯ / FIRST ROUND OF PEER-REVIEW

Scientific quality: Grade C (Fair)

Language quality: Grade B (Minor language polishing)

Re-review: Yes

The management of blunt splenic trauma remains highly relevant in modern emergency surgery. Given the growing trend toward organ-preserving strategies, this study is timely and addresses important clinical needs. However, it would be valuable to clarify why the Vietnamese population is of particular interest—for instance, due to high rates of road traffic accidents (especially motorcycle-related injuries), limited resources for emergency surgery, or other local factors influencing treatment protocols.

While the study does not propose fundamentally novel approaches, it provides a detailed and valuable account of a single-center experience, particularly regarding the high success rate of NOM for Grade III–IV injuries. That said, the unique factors contributing to this success (e.g., specific protocols for TAE at this institution) are not highlighted.

The study adheres to international standards, with approval from a local ethics committee and declared conflicts of interest/funding sources. For full transparency, the authors should clarify whether informed consent was obtained or state that data were collected anonymously, and consent was waived per local regulations.

The methodology (retrospective analysis, AAST grading, statistical processing in SPSS) is appropriate for the study’s aims. However, exclusion criteria for NOM (e.g., shock, peritonitis) are not specified, and technical details of TAE (embolization materials, selective vs. nonselective approach) are lacking. Including these would enhance the study’s practical relevance.

The conclusions appear overly optimistic for Grade V injuries (60% success with only five cases). A more detailed description of management in these patients is needed: Was NOM strictly applied, or did the institution’s definition include laparoscopy? Additionally, were there complications (e.g., splenic infarction, post-TAE abscesses)? This subgroup may hold the key to the study’s novelty.

Terminology aligns with accepted standards (AAST, NOM, TAE), but there are minor errors (e.g., haemoperitoneum → hemoperitoneum in Table 4).

Non-normally distributed data should be presented as medians with interquartile ranges.

Consider adding visual aids (e.g., histograms, box plots) to improve data interpretation, pending editorial approval.

The manuscript is well-structured, tables are informative, and references (2019–2022) are up-to-date and include key publications. The study may be suitable for publication after revisions.

Recommendation after the first round of peer-review: minor revision.

ВТОРОЙ РАУНД РЕЦЕНЗИРОВАНИЯ /SECOND ROUND OF PEER-REVIEW

Thank you for your careful attention to the previous comments and for revising the manuscript. Your efforts have significantly improved the quality of the work. However, several critical aspects require further clarification to enhance scientific rigor and clarity.

The conclusions now acknowledge the limited sample size (n=5) for Grade V injuries, but data on complications (e.g., splenic infarction, abscesses) remain absent. This is crucial because Grade V injuries involve splenic artery damage. The authors mention one case of traumatic aneurysm and contrast extravasation (indicating active bleeding) in other cases, managed solely via embolization. However, embolization of the splenic artery typically reduces blood supply to the spleen, and collateral circulation via short gastric arteries is often insufficient. This may raise concerns among specialists in NOM of splenic trauma.

While the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test is mentioned in Methods, non-normally distributed data (e.g., hospital stay duration) are still presented as mean ± SD in Results.

Recommendations:

- Clarify whether complications occurred in Grade V cases. If none were observed, explain potential reasons (e.g., short follow-up period, compensated collateral circulation, as confirmed by tests).

- Consider consulting vascular or endovascular surgeons/interventional radiologists to validate the methodology and address technical nuances.

- Specify which variables had normal/non-normal distributions in Results.

- For non-normal data, replace mean ± SD with median [IQR] or Me (P25; P75)

Addressing these points will strengthen the manuscript’s validity and appeal to an international audience. Once revised, the study will be suitable for publication. Thank you for your cooperation and understanding.

РЕЦЕНЗЕНТ C / REVIEWER C

Инициалы / Initials | 1218_В

|

Научная степень / Scientific degree | Доктор медицинских наук / Dr. of Sci. (Medicine)

|

Страна/территория / Country/Territory | Россия / Russia

|

Дата рецензирования / Date of peer-review | 21.05.2025

|

Число раундов рецензирования / Number of peer-review rounds | 1 |

Финальное решение / Final decision | Принять к публикации / Acccept

|

ПЕРВЫЙ РАУНД РЕЦЕНЗИРОВАНИЯ / FIRST ROUND OF PEER-REVIEW

Scientific quality: Grade B: Good

Language quality: Grade B (Minor language polishing)

Re-review: No

The article is devoted to an urgent problem of modern life – trauma, the undisputed leader of mortality among young people. One of the causes of death in abdominal trauma is massive blood loss from damaged parenchymal organs. The spleen suffers more often than other parenchymal organs of the abdominal cavity. Therefore, timely and effective treatment of spleen injuries is extremely important to improve the treatment outcomes of injured patients.

The study included 136 patients with injured spleen who were treated in the same hospital for three years, which indicates the sufficient surgical experience of this medical institution, and the reliability of approaches used in the treatment of patients with abdominal trauma. The number of clinical cases studied is quite sufficient to determine trends and directions for further research.

The material is systematized and presented quite satisfactorily and is accessible to perception. Generally accepted tools have been selected and used for statistical processing of the obtained results, which makes it possible to interpret them correctly.

The results obtained do not pretend to be sensational, but they are modern and quite interesting. Their discussion is in the context of the results of other studies dealing with this problem and does not contradict them. The title of the article fully reflects its content.

РЕЦЕНЗЕНТ D / REVIEWER D

Инициалы / Initials | 1218_В

|

Научная степень / Scientific degree | Доктор медицинских наук / Dr. of Sci. (Medicine)

|

Страна/территория / Country/Territory | Россия / Russia

|

Дата рецензирования / Date of peer-review | 27.05.2025

|

Число раундов рецензирования / Number of peer-review rounds | 1 |

Финальное решение / Final decision | Принять к публикации после небольшой доработки / Minor revision.

|

ПЕРВЫЙ РАУНД РЕЦЕНЗИРОВАНИЯ / FIRST ROUND OF PEER-REVIEW

Scientific quality: Grade B: Good

Language quality: Grade B (Minor language polishing)

Re-review: No

The article should detail the principles of non-operative management in the context of blunt splenic injuries. What treatment algorithms and methodologies are recommended?

РЕКОМЕНДАЦИИ НАУЧНЫХ РЕДАКТОРОВ ЖУРНАЛА / RECOMMENDATIONS

OF THE SCIENTIFIC EDITORS OF THE JOURNAL

Title

- Revise the title of the manuscript to reflect the main finding or distinctive feature of your study. The current title closely mirrors that of an already published work (reference 6 in the bibliography). The title should be no more than 150 characters with spaces. Avoid abbreviations in the title.

Article highlights

- Add the ‘Article highlights’ section that contains 3 to 5 key messages.

Aim

- Clearly define the aim of the study. Only one aim is possible in the article. The aim should be the same both in the abstract and in the main text

Methods

- Add inclusion, non-inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Provide study flowchart.

- Provide the sample size justification, taking into account the study design, expected effect size, statistical power, and significance level.

- Add the criterion used to assess the normality of the distribution.

- As you perform multiple comparisons, add appropriate multiple comparison tests.

Results

- Add p-value for each comparison in table 2.

- Clarify the method which is used to get p-value for table 3. In the case of multiple comparisons, it is necessary to apply appropriate multiple comparison tests and report the significance level adjusted for multiple testing. Add p-value for each comparison.

Technical requirements

- Add information about all authors (full surname and name, academic degree and title (if any), position, place of work (or study), ORCID).

- For corresponding author provide full first and family (sur)names, abbreviated title (e.g., MD, PhD), affiliated institute’s name and complete postal address (including zip code).

- Specify authors’ contribution.

- Place all metadata before the main text.

- Provide ‘List of abbreviation’ before the main text.

- All abbreviations used in the article should be decrypted after they were firstly mentioned.

- All abbreviations used in the tables should be defined in notes accompanying each respective table.

- Place tables in the main text after they were firstly mentioned.