Scroll to:

Validation of specially designed and artificial intelligence-based 3D head model for training of Gasserian ganglion puncture

https://doi.org/10.47093/2218-7332.2025.1237

Abstract

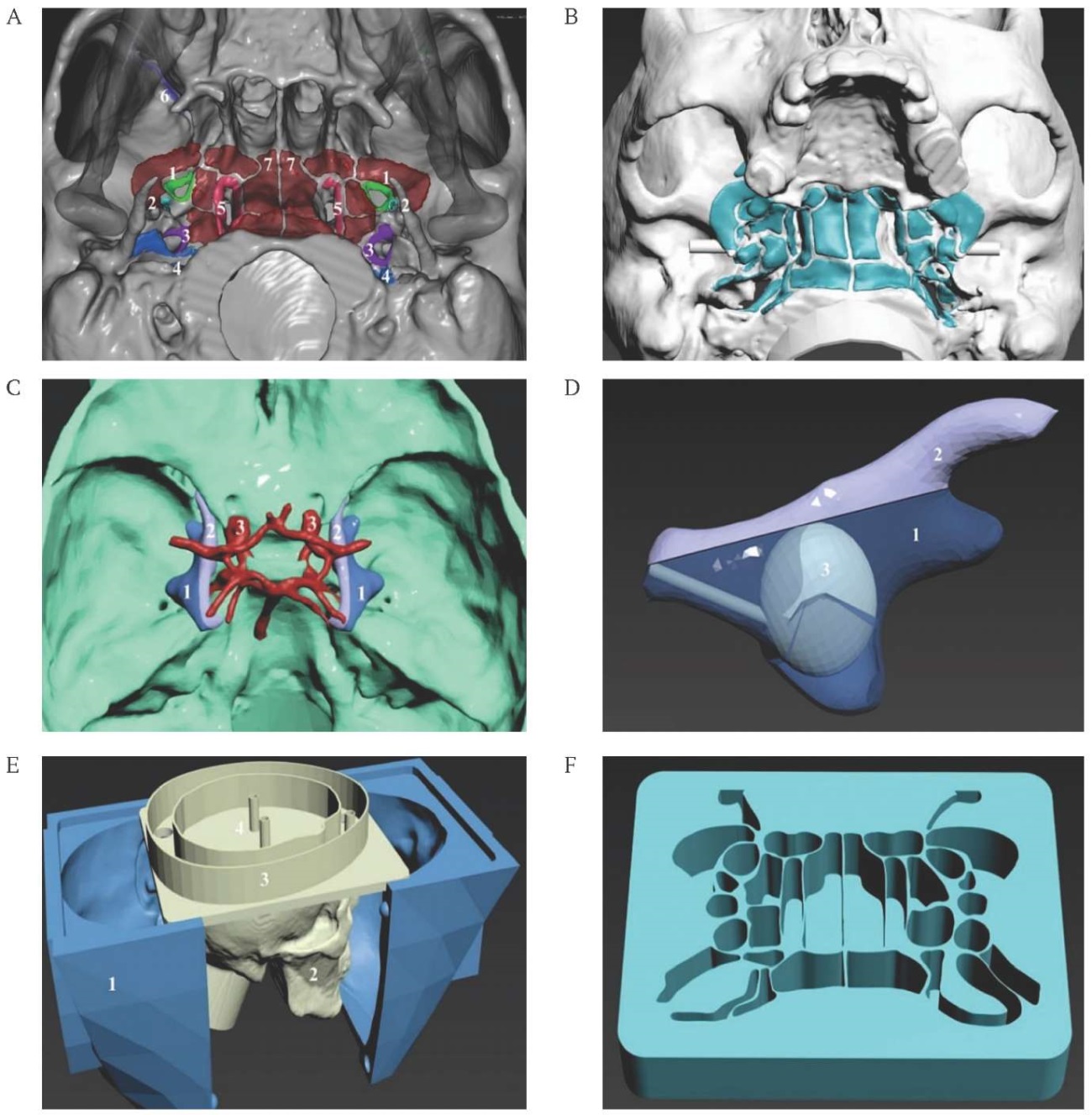

Aim. To design, develop and validate a 3D head simulation model for foramen ovale puncture, incorporating computer vision-based artificial intelligence (AI) technologies.

Materials and methods. A 3D simulation model with AI integration was developed in the prototyping laboratory. Its effectiveness for surgical training was evaluated by two groups: neurosurgeons with five or more years of experience (n = 10) and residents (n = 28). Training outcomes were assessed using the following parameters: intervention time, number of puncture attempts until they achieved the first one without any complications, number of complications involving critical anatomical structures. The validity was assessed using a Likert scale.

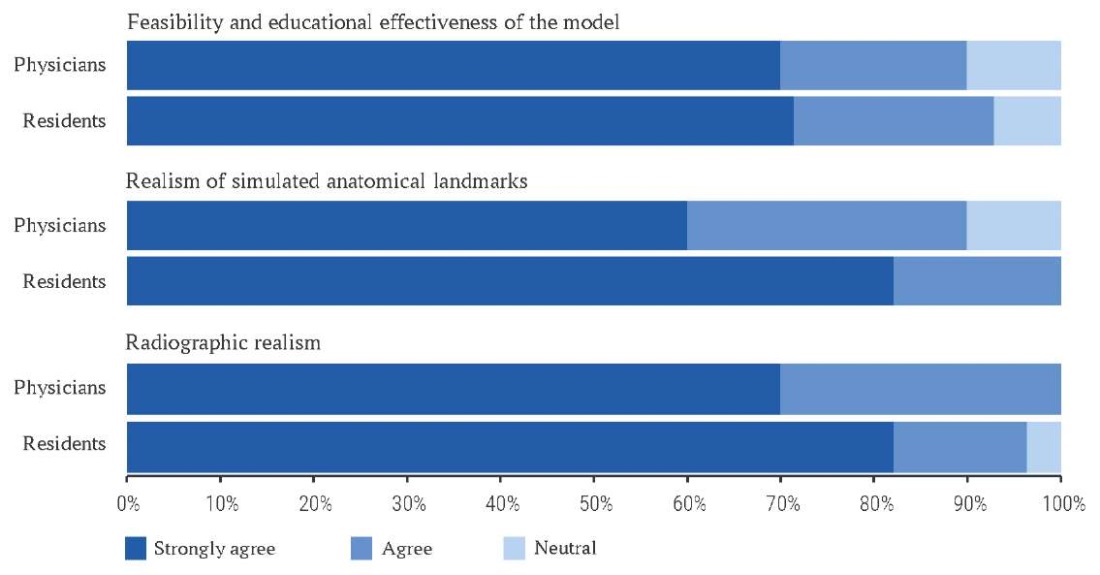

Results. Before the training session, the groups differed in terms of the time spent on the procedure, the number of puncture attempts and the number of complications involving critical anatomical structures. Post-training intervention time decreased by 50% in both groups, the number of puncture attempts reduced by 50.0% in physicians and by 60.3% in residents. The cumulative number of complications declined by 57.8% in physicians and by 59% in residents. Likert scale analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between groups across all parameters. The feasibility and educational effectiveness of the model were rated as 4 or 5 by 90% of participants in both groups. Anatomical realism received a score of 4 or 5 from 90% of physicians and 100% of residents. Radiographic realism received a score of 4 or 5 from all participants. The cost of creating a simulator, excluding the cost of a 3D printer, was 22,685 rubles.

Conclusion. The developed 3D simulation model with AI integration significantly improved training outcomes both in physicians’ and residents’ groups. The use of standard prototyping equipment provides a cost-effective, radiation-free alternative for widespread implementation in neurosurgical education.

Keywords

Abbreviations:

- AI – artificial intelligence

- FO – foramen ovale

- GG – Gasserian ganglion

The paradigm of a competency-based surgical education is intrinsically linked to the structured training of specialists [1]. A key strategy for preparing neurosurgical trainees involves combining rigorous theoretical instruction with accessible practical experience [2]. Today, challenges in literature accessibility are largely addressed through global open-access archives of medical publications [3]. However, the limited duration of residency and the potential for fatal complications arising from intraoperative neurosurgical errors constrain the acquisition of hands-on surgical skills [4].

In the current literature, little attention is paid to simulation models for training puncture techniques in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia [5]. D.B. Almeida et al. [6] described a method for creating a model for practicing puncture treatment of trigeminal neuralgia based on a cadaveric skull, in which the authors used a skull with a movable lower jaw actuated by springs, preserved spatial dimensions for the silicone structure, and applied a latex mask to enhance realism. A similar model based on a cadaveric skull was presented by Y.Q. He et al. in 2014 [7], with the distinctive feature of incorporating a silicone Gasserian ganglion (GG).

While cadaveric dissection remains the gold standard for technical training, legal, ethical, and financial constraints have led to a yearly decline in cadaver availability [5]. The active integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and engineering technologies in medicine has transformed approaches to surgical education [8].

The procedural target in trigeminal neuralgia punction is the GG, which is most safely and effectively accessed via the foramen ovale (FO) of the skull base [9]. Performing GG puncture under radiologic guidance requires additional hand-eye coordination, as it relies on fluoroscopic trajectory alignment without direct visual feedback. However, fluoroscopic guidance limits training time due to the negative effects of ionizing radiation [10]. Emulating C-arm functionality via computer vision technologies can offer a safe and accessible training solution.

Aim of the study: to design, develop and validate a 3D head simulation model for FO puncture, incorporating computer vision-based AI technologies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study consisted of two parts: the design of a 3D head model using AI (01.05–17.06.2024), and the evaluation of its training validity (15.08–01.10.2024).

Part 1. Development of the 3D head model

Pseudonymized magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography data in DICOM format from one patient with trigeminal neuralgia were utilized to construct the 3D model. A detailed research protocol was developed to guide the modeling of specific anatomical structures: cerebral arteries (based on 3D time of flight magnetic resonance angiography), cranial nerves (fast Spoiled Gradient Echo based on magnetic resonance imaging), and the skull (computed tomography imaging).

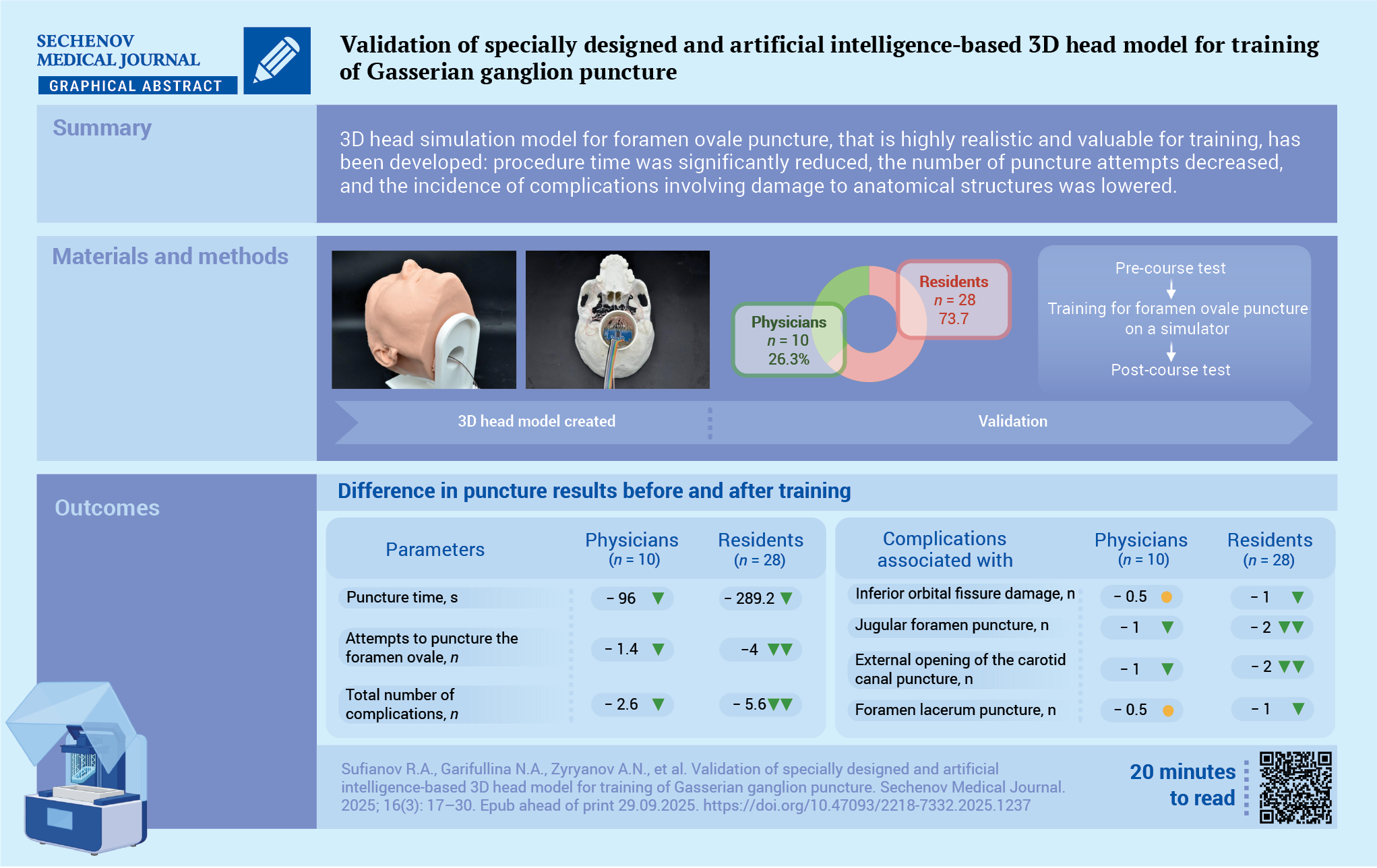

Using the Inobitec DICOM Viewer software (Inobitec DICOM Viewer Pro licensed software, Inobitec LLC, Russia), artifact removal and segmentation were performed for the following structures based on native DICOM data: the skull base, contact zones in the skull base region (including the inferior orbital fissure, jugular foramen, external opening of the temporal carotid canal, lacrimal foramen and spinous foramen), GG, and internal carotid artery (Fig. 1A).

The segmented data were exported in STL format to Autodesk 3D Max software (3ds Max licensed software, Autodesk Inc., USA), where the following elements were modeled: a hinge mechanism to simulate the mobility of the temporomandibular joint, GG (including maxillary, mandibular, and orbital branches), a non-anatomical Meckel’s cave (a cavity within the GG aligned with the triangular plexus projection), a tube for housing electronic components, a stand for the 3D head model, a LED screen, negative skin molds for silicone casting, and custom molds for silicone containers (Fig. 1B–F).

FIG. 1. 3D head model created by Inobitec and Autodesk 3D Max software.

A. The 3D model of the skull base with highlighted contact and non-contact zones (Inobitec software): 1 – foramen ovale (green color), 2 – foramen spinosum (turquoise color), 3 – external opening of the carotid canal (lilac color), 4 – foramen jugulare (blue color), 5 – foramen lacerum (pink color), 6 – inferior orbital fissure (dark blue), 7 – adjacent non-contact zones (red color).

B. The 3D model of the skull base with highlighted contact and non-contact zones (both marked in turquoise, Autodesk 3D Max software).

C. The 3D model of the Gasserian ganglion and internal carotid artery (Autodesk 3D Max software): 1 – maxillary and mandibular zones of the Gasserian ganglion, 2 – ophthalmic branch of the Gasserian ganglion, 3 – internal carotid artery.

D. The 3D model of the Gasserian ganglion with a simulated Meckel’s cave (Autodesk 3D Max software): 1 – maxillary and mandibular zones of the Gasserian ganglion, 2 – ophthalmic branch of the Gasserian ganglion, 3 – non-anatomic Meckel’s cave (cavity inside the Gasserian ganglion in the triangular plexus projection).

E. The 3D printed form for silicone casting of the external part of the skin in collapsible mold (Autodesk 3D Max software): 1 – 3D printed model of the negative mold for skin filling, 2 – 3D model of the skull for skin filling, 3 – container for additional volume of silicone, 4 – ventilation holes for degassing.

F. The 3D model of the LED screen (Adobe 3D Max software).

Autodesk 3ds Max data were exported to PrusaSlicer software (open-source license, Prusa Research, Czech Republic) to prepare for printing on a Hercules Strong DUO 3D printer (IMPRINTA Russia) with a TwinHot dual extruder head, using fused deposition modeling technology. The resulting file was saved in GCODE format.

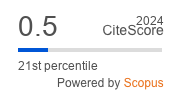

Two extruders were used simultaneously to fabricate the skull base. The first extruder, loaded with white ABS plastic, printed the main non-electroactive volume of the skull with 100% filling to simulate the density of the bone structure. The second extruder used electrically conductive black filament U3 Flex Conductive to print the electroactive areas of the skull. The conductive properties of the material were achieved through its composition, which included thermoplastic polyurethane and carbon nanotubes. In addition, 3D models of internal carotid artery and GG were printed using the conductive filament. In contrast, components such as the electronic tube housing, the head model stand, LED screen frame, negative skin molds for silicone casting, and negative molds for tip production were printed with PLA plastic.

To create skin models, the printed silicone molds were treated with a wax-based release spray lubricant. For casting, Ecoflex 00-10, a platinum-based silicone system, was mixed with POLYMER O coloring pigment paste and degassed using a vacuum compressor prior to pouring. The silicone system was poured into the prepared mold. The skin model was bonded to the skull using SIL-POXY, a silicone-based adhesive. For simulation of the dura mater, the Platset 20 silicone system was applied to the inner surface of the skull model. To recreate the Meckel cavity, the negative tip mold was coated with silicone to form a balloon-like structure, which was fixed to the electronic tube with SIL-POXY adhesive. The silicone tube was connected to a 20 mL syringe that delivered pressurized water.

After preparation of all components, the electroactive zones were connected to the electronic unit with flexible copper fluoroplastic-insulated stranded wires. Light and sound signaling of instrument contact detection with electroactive zones of the skull base, as well as with 3D models of the internal carotid artery and GG, was carried out by detecting electrical resistance in the “conductive plastic – puncture needle” circuit (Fig. 2A–F).

FIG. 2. The electronic part of the 3D head model for practicing foramen ovale puncture.

A. The silicone 3D head model with electronics unit.

B. The 3D printed head model with electroactive zones printed with black U3 Flex Conductive filament.

C. The electronics block of a 3D skull model based on ARDUINO microcontroller.

D. The electronics block of the LED screen based on ARDUINO microcontroller.

E. The LED screen.

F. The scheme of the LED screen: 1 – foramen ovale, 2 – foramen spinosum, 3 – external opening of the carotid canal, 4 – foramen jugulare, 5 – foramen lacerum, 6 – inferior orbital fissure, 7–14 – adjacent non-contact zones.

In addition to the conductivity of the needle, a special QR code was printed and attached to the end of the needle to apply computer vision technology.

The “conductive plastic – puncture needle” circuit was implemented via a programmable multichannel electronic unit based on Arduino Nano microcontroller (open-source hardware and software platforms, Arduino Software, Italy). Expansion of analog input capacity was achieved using a 16-channel multiplexer (CD74HC4067), while output expansion for LED signal indicators was facilitated using 74HC595 shift registers. LED indication was realized by means of SMD 5730 type LEDs and 15 Ohm current-limiting resistors. A circuit diagram of the 3D head model operation based on the ARDUINO microcontroller is presented in Supplement A (Supplementary materials on the journal’s website https://doi.org/10.47093/2218-7332.2025.1237-annex-a).

White LEDs, responsible for detection of the skull base zones, were installed at designated positions on the LED screen, each separated by plastic dividers to minimize the scattering of the light flux around the perimeters of certain zones. Additionally, green LED (Led1) and red LED (Led2) were mounted at the base of the LED screen to indicate puncture needle contact with the GG and internal carotid artery, respectively. The total cost of consumables was 22,685 rubles.

The time spent on modeling was 5 days, production of the 3D model – 2 days, work with electronics and programming – 4 days. The total cost of consumables was 22,685 rubles (Supplementary materials on the journal’s website https://doi.org/10.47093/2218-7332.2025.1237-annex-b).

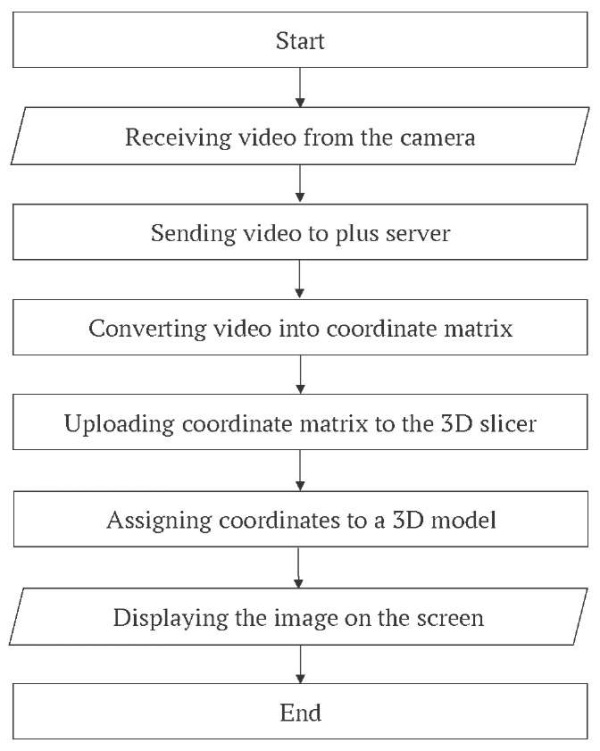

Finally, a portable neuronavigation system was developed to reduce radiation exposure for trainees. To simulate the puncture intervention, an integrated hardware-software complex utilizing computer vision technologies was employed. Video tracking of the surgical instrument was achieved by detecting fractal markers in the form of QR codes affixed to the instrument. The streaming image was captured and transferred to a personal computer, where it was processed using the PLUS Server application (open-source software, Plus Toolkit Community and PerkLab) [11]. In this system, AI algorithms convert the incoming video stream into a matrix of spatial coordinates. These coordinates are subsequently transferred to a dedicated visualization platform – 3D Slicer software (open-source license) [12]. The resulting spatial data were mapped onto a virtual environment within 3D Slicer, where the coordinates were assigned to a 3D model of the surgical instrument. This allowed dynamic visualization of its interaction with the 3D training model of the head on the monitor screen. Two essential models were integrated into the 3D Slicer environment: the virtual surgical instrument and the static head model, reconstructed from patient-specific DICOM data. The head model is static, while the surgical instrument moved in real time according to the physical instrument’s position, thereby simulating C-arm-like visualization during the simulated procedure (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3. The block diagram of computer vision technology.

Part 2. Validation of the training model of the foramen ovale puncture simulator

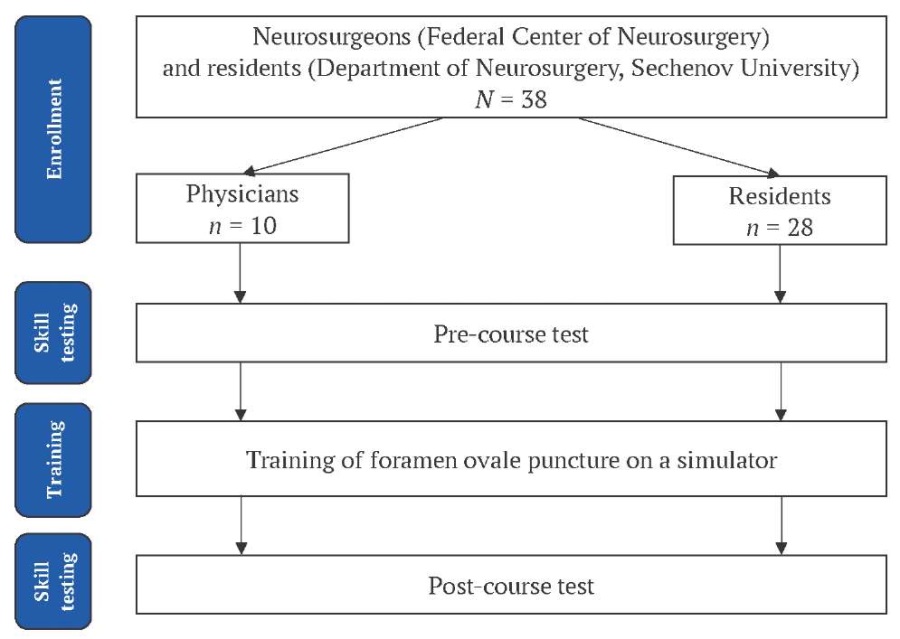

A total of 38 participants, 10 experts (neurosurgeons with more than 5 years of experience) of the Federal Center of Neurosurgery (Tyumen) and 28 residents of the Department of Neurosurgery of the Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), whose clinical site is located at Federal Center of Neurosurgery, underwent the simulation program (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4. Study flowchart.

Inclusion criteria:

- age from 23 to 60 years;

- theoretical knowledge of the topographic anatomy of the skull base;

- theoretical knowledge of the radiographic orientation of the FO of the skull;

- no prior involvement in the development of the simulation model;

- a written voluntary informed consent to participate in the study.

Non-inclusion criterion:

- mental disorders affecting learning (n = 0).

The training took place in a laboratory setting is presented in the video file Supplement С (Supplementary materials on the journal’s website

https://doi.org/10.47093/2218-7332.2025.1237-annex-c).

The results of the FO puncture were evaluated befo e and after training period using the following parameters:

- intervention time;

- number of puncture attempts;

- number of complications during the puncture involving anatomical structures located at the skull base (the inferior orbital fissure, jugular foramen, external opening of the temporal bone carotid canal, foramen lacerum, and foramen spinosum) as well as in the region of the middle cranial fossa (the first branch of the trigeminal nerve and the cavernous segment of the internal carotid artery).

Before and after training, each participant performed a series of puncture attempts until they achieved the first one without any complications. Once this had been achieved, they stopped and recorded the result. The maximum number of attempts was limited to ten.

Also, participants completed a post-training questionnaire based on a Likert scale to access the perceived feasibility and educational value of the simulator, the anatomical realism of landmarks and radiographic realism with scores: strongly agree (5), agree (4), neutral (3), disagree (2), strongly disagree (1) [13].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported as absolute frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and as medians with interquartile ranges (25th; 75th percentile) for ordinal or non-normally distributed continuous variables. For normally distributed continuous variables, data were expressed as mean with standard deviation. Normality was assessed with the Shapiro–Wilk test and verified visually using Q–Q plots and histograms.

The median values were calculated from multiple puncture attempts performed by each participant within each training phase, and then group medians with interquartile ranges were determined across all participants in each group. Between-group comparisons were performed with a two-tailed independent Student’s t-test for normally distributed data or the Mann–Whitney U-test for non-normally distributed data. Comparisons of paired data befo e and after training were performed using the paired Student’s t-test for normally distributed differences or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for non-normally distributed differences. Five-level Likert responses were compared between groups with the two-sided Fisher–Freeman-Halton exact test (5×2 contingency tables). For sensitivity analysis, Likert scores were dichotomized (≥ “Agree” vs. ≤ “Neutral”), and a two-sided Fisher’s exact test (2×2) was applied. All tests were two-tailed, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted in R version 4.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Analysis of puncture performance befo e and after training revealed statistically significant improvement across all evaluated parameters in both groups (Table). Following the training, puncture time was reduced by approximately half in both groups. The number of puncture attempts befo e the first successful, complication-free attempt was reduced by 50% in the physicians’ group and by 60.3% in the residents’ group.

Table. Puncture results befo e and after training

Parameter | Physicians (n = 10) | p value | Residents (n = 28) | p value | ||

Before | After | Before | After | |||

Puncture time, s | 186.0 ± 77.2 | 90.0 ± 51.0 | <0.001 | 527.1 ± 135.0b | 237.9 ± 82.4b | <0.001 |

Attempts to puncture the foramen ovale, n | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | <0.001 | 6.6 ± 2.1b | 2.6 ± 1.0b | <0.001 |

Total number of complications, n | 4.5 ± 1.6 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | <0.001 | 9.5 ± 3.3b | 3.9 ± 1.7 b | <0.001 |

Complications associated with: | ||||||

inferior orbital fissure damage, n | 0.5 (0; 1.75) | 0 (0; 0) | n.s. | 2 (0.75; 3)a | 1 (1; 2)b | <0.05 |

jugular foramen puncture, n | 1 (0.25; 1) | 0 (0; 1) | n.s. | 3 (2; 4)b | 1 (1; 2)b | <0.001 |

external opening of the carotid canal puncture, n | 1 (0.25; 1) | 0 (0; 0) | <0.05 | 2 (1; 3)a | 0 (0; 0) | <0.001 |

foramen lacerum puncture, n | 0.5 (0; 1) | 0 (0; 1) | n.s. | 1 (0; 2) | 0 (0; 1) | <0.001 |

foramen spinosum puncture, n | 0 (0; 0) | 0 (0; 0) | n.s. | 0 (0; 1) | 0 (0; 0.25) | n.s. |

puncture of the first branch of the trigeminal nerve, n | 0.5 (0; 1) | 0 (0; 0.75) | n.s. | 0 (0; 1) | 0 (0; 0.25) | n.s. |

internal carotid artery puncture, n | 0 (0; 1) | 0 (0; 0.75) | n.s. | 0 (0; 1) | 0 (0; 0) | n.s. |

Notes: a p < 0.05, b p < 0.001 when compared to a group of physicians at the same point of the study.

n.s. – not significant.

The total number of complications after training decreased by 57.8% in the physicians’ group and by 59.0% in the residents’ group. Initial complication rates associated with inferior orbital fissure damage, jugular foramen puncture and puncture of external opening of the carotid canal were higher in the residents’ group. While initial frequency of other complications (foramen lacerum puncture, puncture of the first branch of the trigeminal nerve, puncture of the internal carotid artery and foramen spinosum puncture) was low and similar both in physicians’ and residents’ groups (Table).

Following training, the complication rate related to puncture of the external opening of the carotid canal decreased by 88.9% in physicians and by 94.9% in residents, resulting in no statistically significant difference between the two groups post-training (Table). Complications related to puncture of the inferior orbital fissure and jugular foramen decreased by 75.0% and 50.0%, respectively, in physicians, and by 35.3% and 51.9%, respectively, in residents; however, the rates among residents remained significantly higher compared to those of physicians. Other puncture-related complications decreased as follows: foramen lacerum – by 42.9% in physicians and 68.4% in residents; foramen spinosum – by 0% and 44.4%, respectively; first branch of the trigeminal nerve – by 50.0% and 27.3%; internal carotid artery – by 40.0% and 50.0%. Post-training complication rates for these structures were comparable between physicians and residents.

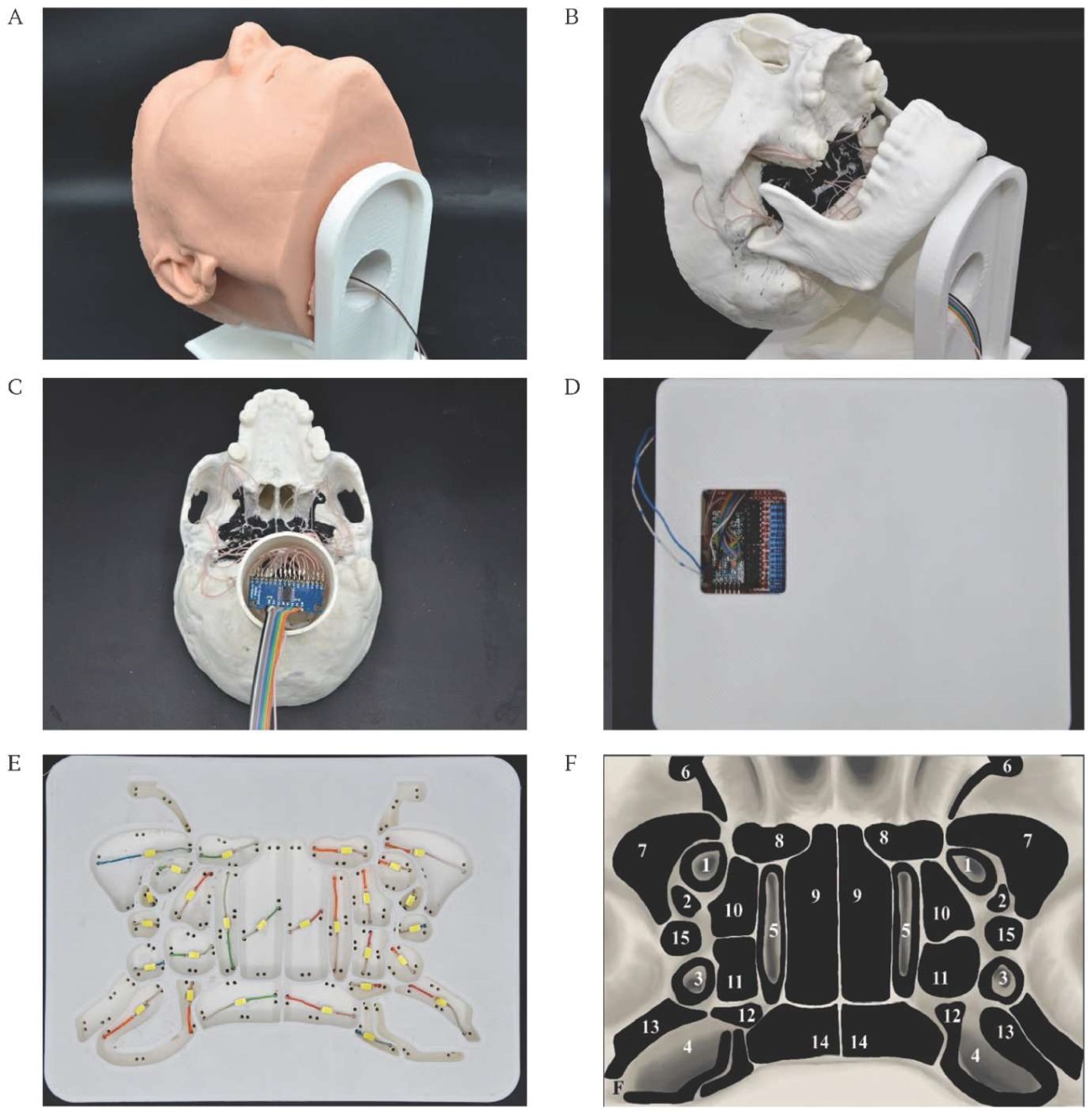

The feasibility and construct validity of the simulator was confirmed by the Likert scale. Both groups rated the simulator as “useful for educational purposes” and “realistic” from anatomical and radiographic points of view.

The perceived feasibility and educational value of the simulator, the anatomical realism of landmarks and radiographic realism, assessed by the Likert scale, received equivalent ratings from both the physicians’ group and the residents’ group (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5. The training results according to the Likert scale.

DISCUSSION

Various puncture-based interventions for trigeminal neuralgia share a common technical approach: accessing the GG via FO puncture [14]. Despite the technical simplicity of performing FO puncture, the lack of surgical skills may lead to serious complications [15].

The iatrogenic nature of such complications is most frequently attributed to the surgeon’s insufficient competence, leading to anatomical disorientation and difficulty maneuvering the puncture needle under fluoroscopic control, primarily due to inadequate hand-eye coordination [10]. To improve a surgeon’s competence in puncture-based interventions, it is necessary to provide quality preoperative training in a safe environment [16].

The present study demonstrated the effectiveness of integrating engineering technology and AI in creating a 3D simulator for teaching FO puncture in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. The high Likert scale scores for the educational effectiveness of the simulator (70.0–71.4% of participants selected the maximum score), realistic anatomical landmarks (60.0–82.1%) and radiological visualization (70.0–82.1%) confirm the high quality of the developed model. The results of this study showed a statistically significant improvement in all evaluated parameters in both groups of participants after training on the developed model.

The most encouraging result was a 50% reduction in intervention time in both groups after simulation training despite a significant difference in pre-training scores (difference between physicians and residents 341.1 sec), indicating the development of sustainable practical skills regardless of the participants’ initial training level. Equally important, a reduction in the number of puncture attempts by 50% in physicians and 60.3% in residents indicates improved accuracy in performing the procedure. The more pronounced improvement in the resident group may be due to the greater potential for skill development in less experienced professionals, consistent with the concept of a learning curve in surgery [17][18].

The results of this study showed a significant reduction in the total number of complications (around 60% in both groups), which is a key indicator of the clinical relevance of the developed simulator. A more detailed analysis of the types of complications showed that the greatest improvement was observed for puncture of the foramen jugulare, inferior orbital fissure and external carotid orifice in the resident group. Notably, the initially higher complication rates in the resident group approached those of experienced physicians for most parameters after training. The exceptions were puncture of the first branch of the trigeminal nerve and internal carotid artery, where differences between groups were minimal both befo e and after training. This observation indicates the formation of hand-eye coordination skills and a more accurate understanding of the trajectory of the puncture needle in the areas of the skull base. Formation of the skill of hand-eye coordination in performing various types of surgical interventions has received much attention in the literature [6][19–21]. The 3D model developed in this study accurately reproduces the anatomical location of the FO, functionally significant areas of the skull base, GG and internal carotid artery. Moreover, the use of electrically conductive carbon nanotube materials to create feedback zones provides immediate tactile and visual confirmation of contact with critical anatomical structures, which helps prevent the formation of incorrect motor skills and improves the overall quality of learning.

Training of hand-eye coordination for FO puncture usually requires fluoroscopic guidance with a C-arc, which limits training time due to the negative effects of ionizing radiation [22]. Integrating computer vision into the training of FO puncture on a 3D printed model in our study provides a safe and effective alternative [23–25]. In this study, we developed a computer vision algorithm to detect a QR code attached to the puncture needle, thereby mimicking the functionality of the C-arm and enabling the acquisition of hand-eye coordination skills during FO puncture. Using QR code to track the instrument and creating a virtual environment in the 3D Slicer provides a safe alternative to fluoroscopic guidance, which is especially important for repeated training sessions. Another significant advantage of the developed system is its dependence on standard equipment (webcam and personal computer with graphics processor), which makes it affordable for wide implementation in training centers. The elimination of expensive X-ray equipment significantly reduces the overall cost of training, which opens up opportunities for scalable training.

Excluding the cost of a 3D printer, the cost of creating a simulator is significantly lower than the cost of purchasing and storing cadaver material. For instance, the price of a single cadaveric human head is between $600 and $1000 in the US, Russia and Italy [26–28]. Despite the fact that cadaveric material is the most suitable for training, access to cadaveric heads is limited by thanks to legal and financial restrictions [29]. In addition, the costs of maintaining anatomical laboratories are very high and the establishment of a cadaveric laboratory requires the resolution of a number of issues regarding its location, the acquisition of instruments, the purchase, storage and disposal of cadaveric material, as well as strict inter-institutional co-operation to resolve legislative aspects, which limits the use of this material in the modern educational process [30][31].

Limitations of the study and further research perspectives

The study had a limited sample size (38 participants), which may reduce the statistical significance of the results and their generalizability to a wider population of learners. The model is based on data from a single patient with trigeminal neuralgia, which does not take into account anatomical variations between different patients and may limit the realism of the training process.

Further development of this topic could include the creation of a library of 3D models based on different anatomical variants of the FO to increase the versatility of the simulator, as well as multicenter randomized controlled trials to assess the impact of simulation training on clinical outcomes and patient safety in real-world practice.

CONCLUSION

The conducted study emphasizes the effective integration of engineering technology and AI as a useful and safe tool for teaching puncture-based treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. The results of the study demonstrate that the developed 3D head simulation model is highly realistic and educationally valuable, supported by both quantitative outcomes and qualitative assessments. Procedure time was significantly reduced, the number of puncture attempts decreased, and the incidence of complications involving damage to anatomical structures was lowered. The use of available equipment and open source software solutions makes this technology scalable for widespread implementation in educational institutions, which can significantly improve the quality of neurosurgeon training and, ultimately, patient safety.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Albert A. Sufianov, Rinat A. Sufianov and Nargiza A. Garifullina developed the idea for the research and its design. Albert A. Sufianov, Nargiza A. Garifullina and Margarita F. Chakhmakhcheva performed the scientific literature search and collected the primary data. Aleksandr N. Zyryanov and Anton D. Zakshauskas developed the 3D model and neuronavigation system. Albert A. Sufianov, Rinat A. Sufianov, Nargiza A. Garifullina and Margarita F. Chakhmakhcheva participated in the writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the article.

ВКЛАД АВТОРОВ

А.А. Суфианов, Р.А. Суфианов и Н.А. Гарифуллина разработали основную концепцию и дизайн исследования. А.А. Суфианов, Н.А. Гарифуллина и М.Ф. Чахмахчева выполнили научный поиск литературы и сбор первичных данных. А.Н. Зырянов и А.Д. Закшаускас разработали 3D-модель и систему нейронавигации. А.А. Суфианов, Р.А. Суфианов, Н.А. Гарифуллина и М.Ф. Чахмахчева принимали участие в написании основного текста и редактуре статьи. Все авторы утвердили окончательную версию публикации.

Ethics statements. The study was conducted in accordance with the permission of the Local Ethics Committee of Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University (Sechenov University), No 10-25 dated April 24, 2024.

Data availability. The data confirming the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request. Data and statistical methods used in the article were examined by a professional biostatistician on the Sechenov Medical Journal editorial staff.

Conflict of interest. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Financing. The study had no sponsorship (own resources).

Acknowledgements. The authors thank Ms. Aliya Bukhtoyarova (specialist, Federal Center of Neurosurgery, Tyumen) for translation and editing assistance.

Соответствие принципам этики. Исследование проведено в соответствии с разрешением Локального этического комитета ФГАОУ ВО «Первый МГМУ им. И.М. Сеченова» Минздрава России (Сеченовский Университет) (№ 10-25 от 24.04.2024).

Доступ к данным исследования. Данные, подтверждающие выводы этого исследования, можно получить у авторов по обоснованному запросу. Данные и статистические методы, представленные в статье, прошли статистическое рецензирование редактором журнала – сертифицированным специалистом по биостатистике.

Конфликт интересов. Авторы заявляют об отсутствии конфликта интересов.

Финансирование. Исследование не имело спонсорской поддержки (собственные ресурсы).

Благодарность. Авторы выражают благодарность Алие Бухтояровой – специалисту Федерального центра нейрохирургии (Тюмень) за помощь с переводом и коррекцией рукописи.

References

1. Thomas W.E. Teaching and assessing surgical competence. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006 Sep; 88(5): 429–432. https://doi.org/10.1308/003588406X116927. PMID: 17002841

2. Sachdeva A.K., Tekian A., Park Y.S., Cheung J.J.H. Surgical skills training for practicing surgeons founded on established educational theories and frameworks. Med Teach. 2024 Apr; 46(4): 556–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2023.2262101. Epub 2023 Oct 9. PMID: 37813106

3. Joshi T., Budhathoki P., Adhikari A., et al. Improving medical education: a narrative review. Cureus. 2021 Oct 14; 13(10): e18773. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.18773. PMID: 34804650

4. Koch A., Kullmann A., Stefan P., et al. Intraoperative dynamics of workflow disruptions and surgeons’ technical performance failures: insights from a simulated operating room. Surg Endosc. 2022 Jun; 36(6): 4452–4461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-021-08797-0. Epub 2021 Nov 1. PMID: 34724585

5. Fava A., Gorgoglione N., De Angelis M., et al. Key role of microsurgical dissections on cadaveric specimens in neurosurgical training: Setting up a new research anatomical laboratory and defining neuroanatomical milestones. Front Surg. 2023 Mar 9; 10: 1145881. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2023.1145881. PMID: 36969758

6. Almeida D.B., Hunhevicz S., Bordignon K., et al. A model for foramen ovale puncture training: Technical note. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2006 Aug; 148(8): 881–883; discussion 883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-006-0817-2. Epub 2006 Jun 23. PMID: 16791431

7. He Y.Q., He S., Shen Y.X., Qian C. Clinical value of a self-designed training model for pinpointing and puncturing trigeminal ganglion. Br J Neurosurg. 2014 Apr; 28(2): 267–269. https://doi.org/10.3109/02688697.2013.835379. Epub 2013 Sep 7. PMID: 24628215

8. Buyck F., Vandemeulebroucke J., Ceranka J., et al. Computervision based analysis of the neurosurgical scene – A systematic review. Brain Spine. 2023 Nov 7; 3: 102706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bas.2023.102706. PMID: 38020988

9. Héréus S., Lins B., Van Vlasselaer N., et al. Morphologic and morphometric measurements of the foramen ovale: comparing digitized measurements performed on dried human crania with computed tomographic imaging. An observational anatomic study. J Craniofac Surg. 2023 Jan-Feb; 34(1): 404–410. https://doi.org/10.1097/SCS.0000000000008996. Epub 2022 Sep 6. PMID: 36197435

10. Topalli D., Cagiltay N.E. Eye-hand coordination patterns of intermediate and novice surgeons in a simulation-based endoscopic surgery training environment. J Eye Mov Res. 2018 Nov 8; 11(6): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.16910/jemr.11.6.1. PMID: 33828711

11. Lasso A., Heffter T., Rankin A., et al. PLUS: open-source toolkit for ultrasound-guided intervention systems. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2014 Oct; 61(10): 2527–2537. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2014.2322864. Epub 2014 May 9. PMID: 24833412

12. Fedorov A., Beichel R., Kalpathy-Cramer J., et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012 Nov; 30(9): 1323–1341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2012.05.001. Epub 2012 Jul 6. PMID: 22770690

13. Joshi A., Kale S., Chandel S., Pal D.K. Likert Scale: explored and explained. Curr. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015 Feb 20; 7(4): 396– 403. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJAST/2015/14975

14. Cheshire W.P. Trigeminal neuralgia: for one nerve a multitude of treatments. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007 Nov; 7(11):1565–1579. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.7.11.1565. PMID: 17997704

15. Peris-Celda M., Graziano F., Russo V., et al. Foramen ovale puncture, lesioning accuracy, and avoiding complications: microsurgical anatomy study with clinical implications. J Neurosurg. 2013 Nov; 119(5): 1176–1193. https://doi.org/10.3171/2013.1.JNS12743. Epub 2013 Apr 19. PMID: 23600929

16. Shakur S.F., Luciano C.J., Kania P., et al. Usefulness of a virtual reality percutaneous trigeminal rhizotomy simulator in neurosurgical training. Neurosurgery. 2015 Sep; 11(3): 420–425; discussion 425. https://doi.org/10.1227/NEU.0000000000000853. PMID: 26103444

17. Hopper A.N., Jamison M.H., Lewis W.G. Learning curves in surgical practice. Postgrad Med J. 2007 Dec; 83(986): 777–77

18. Takagi K., Outmani L., Kimenai H.J.A.N., et al. Learning curve of kidney transplantation in a high-volume center: A Cohort study of 1466 consecutive recipients. Int J Surg. 2020 Aug; 80: 129–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.06.047. Epub 2020 Jul 11. PMID: 32659389

19. Kasatkin V., Deviaterikova A., Shurupova M., Karelin A. The feasibility and efficacy of short-term visual-motor training in pediatric posterior fossa tumor survivors. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2022 Feb; 58(1): 51–59. https://doi.org/10.23736/S1973-9087.21.06854-4. Epub 2021 Jul 12. PMID: 34247471

20. Park C.K. 3D-Printed disease models for neurosurgical planning, simulation, and training. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2022 Jul; 65(4): 489–498. https://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2021.0235. Epub 2022 Jun 28. PMID: 35762226

21. Pucci J.U., Christophe B.R., Sisti J.A., Connolly E.S. Jr. Threedimensional printing: technologies, applications, and limitations in neurosurgery. Biotechnol Adv. 2017 Sep; 35(5): 521–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2017.05.007. Epub 2017 May 24. PMID: 28552791

22. Dewan M.C., Rattani A., Fieggen G., et al. Global neurosurgery: the current capacity and deficit in the provision of essential neurosurgical care. Executive Summary of the Global Neurosurgery Initiative at the Program in Global Surgery and Social Change. J Neurosurg. 2018 Apr 27; 130(4): 1055–1064. https://doi.org/10.3171/2017.11.JNS171500. PMID: 29701548

23. Wong C.E., Chen P.W., Hsu H.J., et al. Collaborative humancomputer vision operative video analysis algorithm for analyzing surgical fluency and surgical interruptions in endonasal endoscopic pituitary surgery: cohort study. J Med Internet Res. 2024 Jul 4; 26: e56127. https://doi.org/10.2196/56127. PMID: 38963694

24. Ganni S., Botden S.M.B.I., Chmarra M., et al. A software-based tool for video motion tracking in the surgical skills assessment landscape. Surg Endosc. 2018 Jun; 32(6): 2994–2999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-018-6023-5. Epub 2018 Jan 16. PMID: 29340824

25. Danilov G., Kostyumov V., Pilipenko O., et al. Computer vision for assessing surgical movements in neurosurgery. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2024 Aug 22; 316: 934–938. https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI240564. PMID: 39176945

26. Ciporen J., Lucke-Wold B., Dogan A., et al. Dual endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal and precaruncular transorbital approaches for clipping of the cavernous carotid artery: A cadaveric simulation. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2016 Dec; 77(6): 485–490. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1584094. Epub 2016 May 24. PMID: 27857875

27. Kashapov L.N., Kashapov N.F., Kashapov R.N., Pashaev B.Y. The application of additive technologies in creation a medical simulator-trainer of the human head operating field. IOP Conf Ser: Mater Sci Eng. 2016; 134: 012011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/134/1/012011

28. Santona G., Madoglio A., Mattavelli D., et al. Training models and simulators for endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery: A systematic review. Neurosurg Rev. 2023 Sep 19; 46(1): 248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10143-023-02149-3. PMID: 37725193

29. Xu Y., El Ahmadieh T.Y., Nunez M.A., et al. Refining the anatomy of percutaneous trigeminal rhizotomy: A cadaveric, radiological, and surgical study. Oper Neurosurg. 2023 Apr 1; 24(4): 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1227/ons.0000000000000590. Epub 2023 Jan 23. PMID: 36716051

30. James J., Irace A.L., Gudis D.A., Overdevest J.B. Simulation training in endoscopic skull base surgery: A scoping review. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022 Mar 31; 8(1): 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/wjo2.11. PMID: 35619934

31. Mayol Del Valle M., De Jesus O., Vicenty-Padilla J.C., et al. Development of a neurosurgical cadaver laboratory despite limited resources. P R Health Sci J. 2022 Sep; 41(3): 153–156. PMID: 36018744

About the Authors

R. A. SufianovRussian Federation

Rinat A. Sufianov, Cand. of Sci. (Medicine), Associate Professor, Department of Neurosurgery; neurosurgeon, Department of Neurooncology

8/2, Trubetskaya str., Moscow, 119048;

24, Kashirskoye Highway, Moscow, 115522

N. A. Garifullina

Russian Federation

Nargiza A. Garifullina, postgraduate student, Department of Neurosurgery; neurosurgeon, Department of Admissions and Advisory; Assistant Professor, Department of Pharmacology

8/2, Trubetskaya str., Moscow, 119048;

5, 4 km of Chervishevskogo trakta str., Tyumen, 625032;

54, Odesskaya str., Tyumen, 625023

A. N. Zyryanov

Russian Federation

Aleksandr N. Zyryanov, engineer

5, 4 km of Chervishevskogo trakta str., Tyumen, 625032

A. D. Zakshauskas

Russian Federation

Anton D. Zakshauskas, engineer

5, 4 km of Chervishevskogo trakta str., Tyumen, 625032

M. F. Chakhmakhcheva

Russian Federation

Margarita F. Chakhmakhcheva, student, Institute of Motherhood and Childhood

54, Odesskaya str., Tyumen, 625023

A. A. Sufianov

Russian Federation

Albert A. Sufianov, Dr. of Sci. (Medicine), Professor, Corresponding Member of the RAS, Head of the Department of Neurosurgery; Chief Physician; Director, Educational and Research Institute of Neurosurgery; Professor, Department of Neurosurgery

8/2, Trubetskaya str., Moscow, 119048;

5, 4 km of Chervishevskogo trakta str., Tyumen, 625032;

6, Miklukho-Maklaya str., Moscow, 117198;

Anarkali, Lahore, 54000, Pakistan

Supplementary files

|

1. Supplement А. A circuit diagram of the 3D head model operation based on the ARDUINO microcontroller. | |

| Subject | ||

| Type | Исследовательские инструменты | |

Download

(760KB)

|

Indexing metadata ▾ | |

|

2. Supplement B. Calculation of the cost of making a 3D model of the head. | |

| Subject | ||

| Type | Исследовательские инструменты | |

Download

(814KB)

|

Indexing metadata ▾ | |

|

3. Supplement C. Video demonstrating how to practice the puncture of the foramen ovale. | |

| Subject | ||

| Type | Исследовательские инструменты | |

Download

(645KB)

|

Indexing metadata ▾ | |

Review

Sechenov Medical Journal. Editor's checklist for this article you can find here.

Журнал «Сеченовский вестник» |

| Sechenov Medical Journal |

Рецензии на рукопись |

| Peer-review reports |

Название / Title | Валидация специально разработанной 3D-модели головы с применением искусственного интеллекта для обучения пункции гассерова узла / Validation of specially designed and artificial intelligence-based 3D head model for training of Gasserian ganglion puncture |

Раздел / Section

| НЕЙРОХИРУРГИЯ/ NEUROSURGERY

|

Тип / Article | Оригинальная статья / Original article |

Номер / Number | 1237

|

Страна/территория / Country/Territory of origin | Россия / Russia |

Язык / Language | Английский / English

|

Источник / Manuscript source | Инициативная рукопись / Unsolicited manuscript |

Дата поступления / Received | 05.06.2025 |

Тип рецензирования / Type ofpeer-review | Двойное слепое / Double blind |

Язык рецензирования / Peer-review language | Английский / English |

РЕЦЕНЗЕНТ А / REVIEWER A

Инициалы / Initials | 1237_А

|

Научная степень / Scientific degree | Доктор медицинских наук / Dr. of Sci. (Medicine)

|

Страна/территория / Country/Territory | Россия / Russia

|

Дата рецензирования / Date of peer-review | 19.07.2025 |

Число раундов рецензирования / Number of peer-review rounds | 1 |

Финальное решение / Final decision | принять к публикации / accept

|

ПЕРВЫЙ РАУНД РЕЦЕНЗИРОВАНИЯ / FIRST ROUND OF PEER-REVIEW

Scientific quality: Grade B: Good

Language quality: Grade B (Minor language polishing)

Re-review: No

The article addresses topical issues related to the development of puncture surgical procedures in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. The paper shows in detail that iatrogenic complications are most often associated with insufficient surgeon competence, which leads to anatomical disorientation and difficulty in maneuvering the puncture needle under fluoroscopic control, resulting from a lack of visual-motor coordination skills. To improve the competence of surgeons in the field of puncture neurosurgical interventions, there is an urgent need for high-quality preoperative training in puncture skills in a safe environment. Today, one of the strategic and promising directions for solving the above problems is the introduction of artificial intelligence (AI) and engineering technologies for the development of simulation training models. 3D-printed simulation models are as close to reality as possible in terms of the anatomy and topography of the operated area. The 3D model developed in this work considers the anatomical and topographical location of the oval foramen and Gasser's node, and the use of conductive materials and electronic systems provides feedback when the instrument comes into contact with the target structures. Immediate feedback in case of incorrect needle placement helps to avoid the formation of incorrect skills, which contributes to increased accuracy and quality of training.

However, visual fluoroscopic guidance using a C-arm is necessary to practice visual-motor coordination skills during oval foramen puncture, which limits training time due to the negative effects of ionizing radiation. Integrating computer vision into the training process for oval foramen puncture on a simulated 3D printed model is a safe and effective solution.

Computer vision is a field of AI that focuses on the use of algorithms that allow computers to analyze and understand graphic data, extracting meaningful information from digital images, videos, and other visual inputs. In this work, the authors created a computer vision algorithm for identifying the QR code of the puncture needle, which enabled the emulation of the C-arm and the practice of visual-motor coordination skills during oval foramen puncture. A significant advantage of the developed system is the use of standard equipment (webcam, personal computer with a graphics accelerator), which makes it affordable for widespread implementation in training centers. The absence of the need for expensive X-ray equipment significantly reduces the cost of training and expands the possibilities for practical training of specialists. The integrated collaboration of AI and engineering technologies allows the implementation of physical 3D models for practicing surgical skills, the emulation of a material object into virtual content in real time, and the assessment of a surgeon's readiness for the type of surgical intervention being practiced.

The illustrations are of high quality and easy to understand.

Statistical analysis of punctures before and after training, shown in Table 2, revealed a statistically significant improvement in all indicators in the groups of doctors and residents. According to the results of the study, the initial level of complications in the group of residents was higher, but after training, the indicators were close to those of neurosurgeons.

The realism and construct validity of the simulator were confirmed by residents of the Department of Neurosurgery at the Federal Center for Neurosurgery and neurosurgeons at the Federal Center for Neurosurgery (Likert 4 and 5 points). Residents and practicing neurosurgeons rated the simulator as “easy to use” and “useful” when used to teach puncture methods for treating trigeminal neuralgia.

It should be noted that cadaver material is most suitable for training and allows for a spatial understanding of the anatomy of the puncture corridor from a morphological point of view. However, the limited use of cadaver heads is associated with legal and economic issues. The cost of a single human cadaver head ranges from $600 to $1,000.

The article shows in detail the advantages of modern methods of visualizing the oval foramen. The study focuses on the effective integration of engineering technologies and AI as a useful and safe tool for teaching puncture methods for treating NTN. The results of the study demonstrate that the developed 3D simulation model of the head is highly realistic and has educational value. After simulation training, the duration of the procedure was reduced, the number of puncture attempts decreased, and the number of complications associated with damage to adjacent anatomical structures decreased. These results emphasize the value of using a simulator in the educational process of neurosurgeons.

This work is a definite step forward in the development of surgical treatment for various trigeminal neuralgias and can serve as a teaching aid.

Recommendation after the first round of peer-review: accept.

РЕЦЕНЗЕНТ B / REVIEWER B

Инициалы / Initials | 1237_В

|

Научная степень / Scientific degree | Кандидат медицинских наук / PhD |

Страна/территория / Country/Territory | Япония / Japan

|

Дата рецензирования / Date of peer-review | 15.07.2025 |

Число раундов рецензирования / Number of peer-review rounds | 1 |

Финальное решение / Final decision | принять к публикации / accept

|

ПЕРВЫЙ РАУНД РЕЦЕНЗИРОВАНИЯ / FIRST ROUND OF PEER-REVIEW

Scientific quality: Grade B: Excellent

Language quality: Grade B (Minor language polishing)

Re-review: No

The study presents a report on Gasserian ganglion puncture using AI and 3D models. The procedure is described in detail, effectively demonstrating its efficacy. This video enhances understanding of its efficacy. This paper absolutely deserves to be published in SMJ.

РЕКОМЕНДАЦИИ НАУЧНЫХ РЕДАКТОРОВ ЖУРНАЛА / RECOMMENDATIONS

OF THE SCIENTIFIC EDITORS OF THE JOURNAL

- To provide a clear visual representation of all stages of the study and the groups of participants involved, a flow diagram showing how patients were included in the study is necessary. This enhances transparency, enabling readers to better understand the study design and participant flow.

- To display tables correctly, in accordance with the journal's technical and scientific formatting requirements, the table data must be transposed (i.e. rows containing groups must be converted into columns). This improves readability and ensures compliance with the journal's layout standards.

- To improve clarity and facilitate visual interpretation of the results, it is advisable to present the data from the 'Training results according to the Likert scale' table in graphical format. Using a diagram would make the data more accessible and easier to compare.

JATS XML