Scroll to:

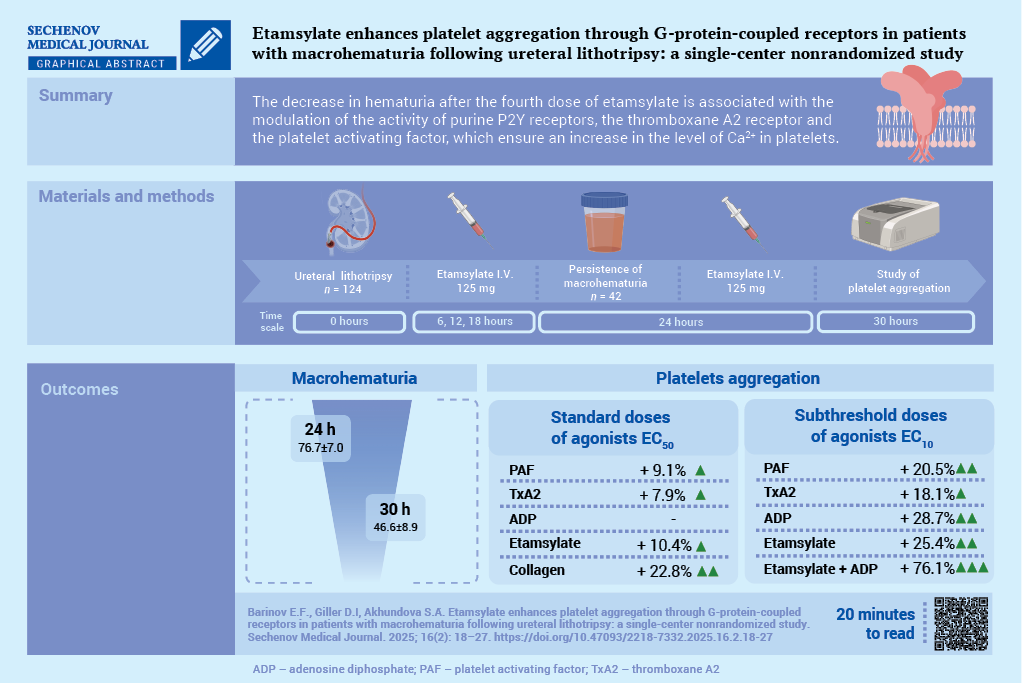

Etamsylate enhances platelet aggregation through G-proteincoupled receptors in patients with macrohematuria following ureteral lithotripsy: a single-center nonrandomized study

https://doi.org/10.47093/2218-7332.2025.16.2.18-27

Abstract

Aim. To evaluate the effect of etamsylate on the activation of signaling pathways involved in the regulation of platelet aggregation in the setting of macrohematuria following ureteral lithotripsy (ULT).

Material and methods. A total of 192 patients undergoing ULT followed by ethamsylate administration were assessed for inclusion in the study. All patients received nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The study included 42 patients (20 men and 22 women; mean age 54.2 ± 15.1 years) who developed macrohematuria following administration of three doses of etamsylate (125 mg I.V. the first dose was administered 6 hours after ULT, followed by further doses every 6 hours). Platelet receptor activity was assessed before and after administration of the fourth dose of ethamsylate (125 mg I.V.) using standard (EC50) and subthreshold (EC10) concentrations of agonists: epinephrine, adenosine triphosphate, adenosine diphosphate (ADP), adenosine, platelet-activating factor (PAF), soluble type IV collagen, and a stable thromboxane A2 analog.

Results. After administration of the fourth dose of etamsylate, macrohematuria significantly decreased compared to baseline values: 46.6 ± 8.9 vs. 76.7 ± 7.0 red blood cells per field of view (p < 0.001). After administration of the fourth dose of etamsylate, upon stimulation with standard agonist concentrations (EC50), there was a significant increase in the activity of the PAF receptor by 9.1% (p = 0.007), the thromboxane prostanoid receptor by 7.9% (p = 0.006), the glycoprotein VI receptor by 22.8% (p < 0.001), and ethamsylate-induced platelet aggregation by 10.4% (p < 0.05). The maximal aggregatory response using subthreshold agonist concentrations (EC10) was observed when platelets were incubated simultaneously with ethamsylate and ADP: amplitude, slope, and AUC (area under the curve) increased by 16.9%, 60.0%, and 54.7%, respectively, compared to isolated stimulation of P2Y receptors (p < 0.05), and by 26.2%, 77.2%, and 65.6%, respectively, compared to incubation with ethamsylate alone (p < 0.05).

Conclusion. The maximal proaggregatory effect of ethamsylate was mediated through P2Y receptors, along with modulation of thromboxane prostanoid and PAF receptors, which promote intracellular Ca²+ elevation

Keywords

Abbreviations:

- ADP – adenosine diphosphate

- AUC – area under the curve

- COX – cyclooxygenase

- GPCR – G-protein-coupled receptors

- GPVI – Glycoprotein VI

- NSAIDs – non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PAF – platelet-activating factor

- ТР – thromboxane prostanoid

- TxA2 – thromboxane A2

- ULT – ureteral lithotripsy

Persistent hematuria after ureteral lithotripsy (ULT) (despite administration of hemostatic agents), remains an important topic in urology [1]. A risk factor for hematuria development is the inhibition of platelet cyclooxygenase (COX), which occurs when non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are prescribed for postoperative analgesia in patients with nephrolithiasis [2]. Impaired canonical signaling related to thromboxane A2 receptor (TP receptor) activation by thromboxane A2 (TxA2) limits the compensatory mechanisms of platelet aggregation [3].

Currently, the synthetic hemostatic agent etamsylate (2,5-dihydroxybenzene sulfonate diethylammonium salt) is widely used in clinical practice to stop bleeding [4]. It works by activating tissue factor at the site of vascular injury, resulting in a reduction in endothelial prostacyclin I2 production, a stimulation of megakaryocytopoiesis, and an increased platelet adhesion and aggregation. In turn, this leads to a cessation or reduction of bleeding [5][6]. An experimental study using canine blood samples demonstrated that etamsylate can inhibit the anticoagulant effect of heparin. Furthermore, it can also exhibit moderate fibrinolytic activity [7].

However, several unanswered questions remain regarding the variability in etamsylate’s hemostatic efficacy: (a) whether postoperative hematuria reduction/cessation is due to receptor activation enhancing P-selectin expression on the platelet membrane and what role etamsylate plays in this process; (b) whether persistent hematuria or its reduction without achieving hemostasis reflects inadequate optimization of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) mediated signaling pathways that promote platelet aggregation.

The aim of the study: to assess the effect of etamsylate on activation of signaling pathways regulating platelet aggregation in macrohematuria following ULT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A single-center, prospective, non-randomized, uncontrolled study was conducted. Consecutive enrollment of patients with renal colic due to urolithiasis was carried out among those hospitalized at the Department of Remote Shock Wave Lithotripsy and Endourology of the M.I. Kalinin Republican Clinical Hospital between January 3, 2022, and November 29, 2024. The sample size was determined during the planning phase and was sufficient to detect a reduction in hematuria by 5 Red blood cells (RBCs) per field of view in urine sediment microscopy within 24 hours after ULT, with a standard deviation of 9, power of 80%, and a significance level of 5%.

Patient Enrollment

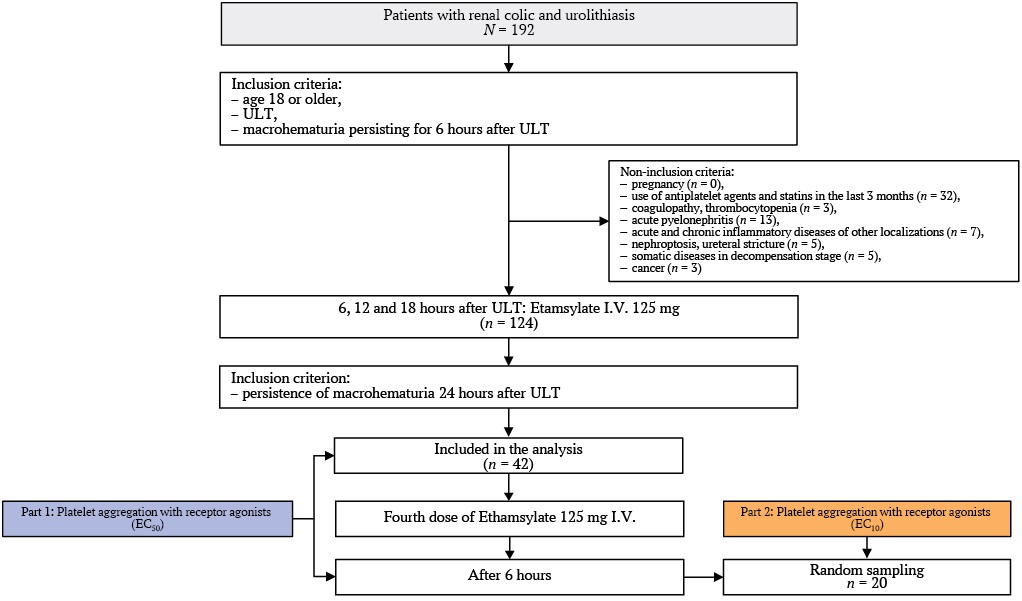

The patient inclusion flowchart is shown in the Figure. A total of 192 patients were assessed to see if they were eligible for the study.

Inclusion Criteria:

- age 18 years or older;

- signed informed consent to participate;

- undergoing antegrade ULT;

- macrohematuria persisting for at least 6 hours post-ULT.

Indications for antegrade ULT included:

- lack of effect from lithokinetic therapy for 7–9 days;

- stone size > 6 mm;

- patient desire for stone removal due to poor tolerance of renal colic pain.

Exclusion Criteria:

- use of antiplatelet agents or statins in the last 3 months (n = 32);

- coagulopathy and/or thrombocytopenia (n = 3);

- acute pyelonephritis (n = 13);

- acute/chronic inflammatory conditions at other sites (n = 7);

- nephroptosis, ureteral stricture (n = 5);

- decompensated somatic disease (n = 5);

- oncological diseases (n = 3).

A total of 68 patients met the exclusion criteria. Of the remaining 124 patients, 82 showed no macrohematuria after three doses of etamsylate. The study continued with 42 patients whose hematuria persisted 6 hours after the third etamsylate dose. A fourth dose of etamsylate was administered to them, and platelet aggregation was evaluated before and 6 hours after this dose (see Fig.). The lack of a control group was due to the clinical necessity of administering etamsylate to all patients with macrohematuria post-ULT.

Fig. Study flowchart.

Note: ULT – ureteral lithotripsy.

Protocol for the Treatment of Urolithiasis

Medical lithokinetic therapy included an α1A-adrenergic blocker (tamsulosin at a dose of 0.4 mg/day).

The choice of antegrade percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) was determined by the following factors: the ability to use larger instruments, a low risk of distal fragment migration in cases of an “impacted” calculus, the possibility of extracting stone fragments without the risk of ureteral damage or avulsion, and a reduced risk of granulation formation in the ureteral mucosa [8]. All ULT procedures were performed under epidural anesthesia with intravenous sedation, with the patient in the prone position, using a rigid nephroscope (basket size 24–26 Fr, operating sheath 27293BD, wide-angle direct vision Hopkins 6° optics 27292AMA, Karl Storz, Germany).

To reduce the duration of the operation and to standardize renal access, after performing retrograde ureteropyelography, ureteral stones were displaced from the middle or upper third of the ureter into the renal pelvis using a rigid ureterorenoscope (length 43 cm, size 8.5 Fr, R.Wolf, Germany). Subsequently, an 8–10 Fr ureteral catheter was placed to deliver contrast medium and irrigation fluid into the renal pelvis. In all cases, the nephrostomy tract was established under combined ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance through the papillae of the lower or middle calyces using telescopic dilators (Karl Storz 27290A, Germany).

The optimal percutaneous access route was selected based on the geometric anatomy of the calculus. Standard lithotripsy and/or lithoextraction were then performed. For stone fragmentation, the following devices were used: an electrohydraulic lithotripter (Urolit, MedLine, Russia), an ultrasonic lithotripter (Karl Storz Calcuson, Germany), a holmium laser lithotripter (Karl Storz Calculase II, Germany), or a combination thereof. The fragmentation settings depended on the density and size of the stone, with density assessed in Hounsfield units (HU) ranging from 300 to 1360 HU on computed tomography. The average stone size was 14.3 ± 0.9 mm (range 8.0 to 30.0 mm). After inspecting the renal pelvis for residual fragments, a 16–18 Fr nephrostomy tube was placed, and a ureteral stent was inserted if necessary. The nephrostomy tube was removed on days 3–7, and the ureteral stent on days 3–20.

For analgesia, all patients received non-selective NSAIDs (sodium diclofenac, 150 mg/day) for two days following ULT. Additionally, to prevent infectious complications, patients were administered antibacterial drugs in accordance with clinical guidelines1.

Protocol for Etamsylate Administration

All enrolled patients received intravenous etamsylate in 4 doses of 125 mg every 6 hours, with a total daily dose of 500 mg (see Fig.).

Assessment of Platelet Aggregation Capacity

The study material consisted of biological fluids collected from patients in the morning on an empty stomach before diagnostic or therapeutic procedures: blood (10.0 mL) from the cubital vein, anticoagulated with sodium citrate solution (9:1 ratio) and 50.0 mL of urine (50.0 mL).

Hematuria was assessed at 6, 18, 24, and 30 hours post-ULT. Given the selection of patients with persistent macroscopic hematuria after three doses of etamsylate, the following time points were chosen for evaluating induced platelet aggregation: before the fourth etamsylate dose (24 hours post-ULT) and six hours after administration (30 hours post-ULT) (see Fig.).

Receptor activity was analyzed in vitro using platelet suspensions prepared from peripheral blood by centrifugation to obtain platelet-rich plasma (PRP) [9]. The platelet count in the samples was 200,000 ± 50,000 cells/μL.

Part 1: Receptor Activity Assessment

The following receptors were studied in all patients using EC50 (half-maximal effective concentration) agonists, which induce 50% aggregation amplitude in healthy individuals: α2-adrenergic receptor (epinephrine, 5.0 μM); purinergic receptors (P2X1 and P2Y) (adenosine triphosphate, 500 μM; adenosine diphosphate (ADP), 5.0 μM); adenosine A2 receptor (adenosine, 5.0 μM); TP receptor (U-46619, a stable TxA2 analog, 7 μM); platelet-activating factor (PAF) receptor (PAF, 150.0 μM); Glycoprotein VI (GPVI) receptor (soluble type IV collagen, 2.0 mg/mL). Agonists sourced from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Germany). Additionally, the in vitro effect of etamsylate (10 μM) as an aggregation stimulator was examined.

Part 2: Signaling Pathway Synergism Modeling

In a subset of 20 patients (randomly selected from 42 enrolled), synergistic signaling pathways were studied 6 hours after the fourth etamsylate dose. Platelets were incubated with: etamsylate (10 μM) and subthreshold (EC10) concentrations of ADP, PAF, U-46619, and their combinations.

Aggregation capacity was evaluated in accordance with European guidelines for standardized aggregometry [10, 11]. Method: Turbidimetric aggregometry using a ChronoLog analyzer (USA). Parameters analyzed: aggregation amplitude (%), maximum slope (%/min) and an area under the curve (AUC).

Statistical Analysis

Normality distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Intergroup differences were analyzed using paired Student’s t-test. Correlation analysis was performed using Pearson’s coefficient, with the Chaddock scale used to determine correlation strength. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All analyses were conducted using MedCalc 18.10.2 (MedCalc Software, Belgium).

RESULTS

The primary results of anthropometric, laboratory, and instrumental evaluations at the hospitalization stage are presented in Table 1. The mean age of enrolled patients was 54 years, with an equal gender distribution. Blood analysis results were within reference ranges. In 62% of cases (n = 26), the calculus was located in the upper third of the ureter, and in 38% (n = 16) in the lower third.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients in both parts of the study

|

Feature |

Part 1 (n = 42) |

Part 2 (n = 20) |

p-value |

|

Age, years |

54.2 ± 15.1 |

53.7 ± 14.2 |

n.s. |

|

Men / Women, n |

20 / 22 |

10 / 10 |

n.s. |

|

Stone in upper third of ureter, n (%) |

26 (62%) |

14 (70%) |

n.s. |

|

Stone in middle third of ureter, n (%) |

16 (38%) |

6 (30%) |

n.s. |

|

Hemoglobin, g/L |

135 ± 10.9 |

137 ± 11.3 |

n.s. |

|

White blood cells (WBC) in blood, ×10⁹/L |

7.2 ± 1.9 |

6.9 ± 2.2 |

n.s. |

|

Platelet count in blood, ×10⁹/L |

228.9 ± 30.5 |

221.3 ± 31.7 |

n.s. |

|

Mean platelet volume, fL |

8.9 ± 1.3 |

8.8 ± 1.5 |

n.s. |

|

WBC in urine, cells/HPF |

11.2 ± 2.3 |

12.1 ± 2.6 |

n.s. |

|

RBC in urine, cells/HPF: |

|||

|

before 1st dose of Etamsylate |

72.5 ± 6.7 |

74.6 ± 8.1 |

n.s. |

|

before 4th dose of Etamsylate |

76.7 ± 7.0 |

75.2 ± 7.8 |

n.s. |

|

after 4th dose of Etamsylate |

46.6 ± 8.9 |

44.9 ± 9.2 |

n.s. |

Note: HPF – high-power field; n.s. – not significant; RBC – red blood cells.

Before the fourth dose of etamsylate, the number of red blood cells in urine was comparable to baseline values (p = 0.42). Six hours after the fourth dose, the number of RBCs in urine decreased to 46.6 ± 8.9 per field of view, representing a 39.3% reduction (p < 0.001). Patients included in part 2 of the study did not differ from the full cohort in major characteristics.

Part 1: Platelet Aggregation with Standard (EC50) Doses of Agonists

Before the fourth dose of etamsylate, hyperreactivity of PAF, TP, and P2Y receptors was observed, along with normoreactivity of P2X1 and α2-adrenergic receptors, and hyporeactivity of A2-adenosine and GPVI (collagen IV) receptors. Six hours after the fourth dose, hyperreactivity of PAF and TP receptors increased by 9.1% (p = 0.007) and 7.9% (p = 0.006), respectively. Hyperreactivity of P2Y receptors persisted, while P2X1 remained normoreactive, and α2-adrenergic hyporeactivity continued. Collagen-induced aggregation increased by 22.8% (p < 0.001). In vitro addition of etamsylate increased aggregation by 10.4% (p = 0.014) (see Table 2).

Table 2. Amplitude of platelet aggregation induced by standard doses of agonists (EC50) before and after the 4th Etamsylate dose

|

Agonist |

Before, % |

After, % |

p-value |

|

PAF |

60.3 ± 7.0 |

65.8 ± 5.4 |

0.007 |

|

TxA2 |

58.5 ± 4.0 |

63.1 ± 3.4 |

0.006 |

|

ADP |

56.8 ± 6.0 |

56.6 ± 9.1 |

n.s. |

|

ATP |

52.6 ± 5.6 |

55.7 ± 9.3 |

n.s. |

|

Epinephrine |

51.5 ± 5.2 |

51.4 ± 3.5 |

n.s. |

|

Adenosine |

43.5 ± 5.8 |

45.0 ± 7.0 |

n.s. |

|

Collagen |

41.7 ± 5.0 |

51.2 ± 5.7 |

<0.001 |

|

Etamsylate |

47.2 ± 6.9 |

52.1 ± 5.1 |

0.014 |

Notes: ADP – adenosine diphosphate; ATP – adenosine triphosphate; EC50 – median effect concentration; n.s. – not significant; PAF – platelet activating factor; ТхА2 – thromboxane A2.

Agonist-receptor complex: adenosine – A2-receptor; ADP – P2Y receptor; ATP – P2X1 receptor; collage – GPVI (Glycoprotein VI) – receptor; epinephrine – α2-adrenoreceptor; PAF – PAF receptor; TxA2 – TP (thromboxane prostanoid) receptor.

Correlation analysis prior to the fourth dose showed weak direct correlations between activities of P2Y and PAF, P2Y and TP, and P2Y and α2-adrenergic receptors, as well as between etamsylate-induced aggregation and activity of PAF, TP, and P2Y receptors. Six hours after the fourth dose, correlation strength between P2Y–PAF and P2Y–TP increased to moderate, and a weak correlation appeared between P2Y and GPVI. The correlation between etamsylate-induced aggregation and P2Y activity increased to moderate strength (see Table 3).

Table 3. Correlation between platelet receptor activity, Etamsylate, and hematuria before and after the 4th Etamsylate dose

|

Factor |

P2Y receptor |

PAF receptor |

TP receptor |

α2-adrenoreceptor |

GPVI – receptor |

|||

|

Before |

After |

Before |

After |

Before |

After |

Before |

After |

|

|

P2Y receptor |

0.43 |

0.51 |

0.41 |

0.57 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

||

|

Etamsylate |

0.39 |

0.58 |

0.32 |

0.44 |

0.31 |

0.41 |

||

|

Hematuria |

–0.6 |

–0.51 |

–0.55 |

|||||

Notes: The Pearson correlation coefficients for which p < 0.05 are given.

GPVI – Glycoprotein VI; PAF – platelet activating factor; ТР – thromboxane prostanoid.

Part 2: Platelet Aggregation with Subthreshold (EC10) Doses of Agonists

In vitro modeling with EC10 doses of PAF, TxA2, ADP, and etamsylate showed comparable aggregation when applied separately (see Table 4).

Table 4. Platelet aggregation induced by subthreshold doses of agonists (EC10) after 4th Etamsylate dose

|

Agonist |

Amplitude, % |

Slope, %/min |

Area under curve |

|

ADP |

13.6 ± 4.8 |

17.5 ± 5.9 |

21.2 ± 7.3 |

|

TxA2 |

13.8 ± 4.3 |

16.3 ± 5.0 |

20.8 ± 7.1 |

|

PAF |

12.7 ± 3.2 |

15.3 ± 5.0 |

20.3 ± 6.2 |

|

Etamsylate 10 µmol/L |

12.6 ± 2.5 |

15.8 ± 3.9 |

19.8 ± 5.5 |

|

plus ADP |

15.9 ± 2.7a,b |

28.0 ± 4.1a,b |

32.8 ± 5.5a,b |

|

plus TxA2 |

15.1 ± 2.3a |

18.5 ± 3.2a |

26.6 ± 6.8a,c |

|

plus PAF |

15.4 ± 2.3a,d |

18.1 ± 2.9a,d |

25.1 ± 5.2a,d |

Notes: p < 0.05 compared to the isolated effects of etamsylate (a), ADP (b), ТхА2 (c), PAF (d).

ADP – adenosine diphosphate; PAF – platelet activating factor; ТхА2 – thromboxane A2.

Co-incubation of etamsylate and ADP produced the highest effect: amplitude, slope, and AUC increased by 16.9%, 60.0%, and 54.7%, respectively, versus ADP alone, and 26.2%, 77.2%, and 65.6% versus etamsylate alone (p < 0.05). Co-stimulation with etamsylate and TxA2 showed a less pronounced effect: slope and AUC were 33.9% and 18.9% lower than the etamsylate–ADP combination (p < 0.005), but AUC was 27.9% higher than TxA2 alone (p = 0.01). Compared to etamsylate alone, combined stimulation with TxA2 increased amplitude, slope, and AUC by 19.8%, 17.1%, and 34.3% (p < 0.05).

Etamsylate combined with PAF produced similar results to the TxA2 combination. Compared to etamsylate alone, values were higher by 22.2%, 14.6%, and 26.8%, respectively (p < 0.05); compared to PAF alone – by 21.2%, 18.3%, and 23.6% (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

It has been established that the reduction of hematuria 30 hours after CLT, caused by inhibition of COX in platelets during systemic administration of etamsylate, is associated with modulation of the activity of P2Y receptors, TP receptor, and PAF receptor, which together increase intracellular Ca²⁺ levels. The most pronounced synergy of etamsylate is observed in the presence of elevated extracellular ADP. The mechanism of platelet activation mediated by Gq-protein is a stereotypical pathway involved in the activation of P2Y receptors, TP receptor, and PAF receptor. Despite the long-standing clinical use of etamsylate, interest in its potential to enhance hemostatic effects remains high [12][13]. On the one hand, this reflects recognition of its pharmacological capabilities; on the other hand, it points to an incomplete understanding of the molecular mechanisms of its action.

Ongoing discussions have led to a consensus that etamsylate is considered an effective second-line agent (after tranexamic acid) for stopping hemorrhage [14]. The observed reduction in postoperative blood loss during combined administration of tranexamic acid and etamsylate [15] has intensified interest in the targeted mechanisms of hemostasis regulation. Attempts to explain the mechanisms of action of etamsylate date back to 2000 [16], when the role of P-selectin–dependent mechanisms in platelet adhesion was demonstrated, essentially indicating a pro-aggregatory effect of the drug. To this day, the variability of the biological effect of etamsylate remains unclear [17]. It is assumed that its effect is mediated by GPCRs, which transmit and amplify signals to intracellular effectors [18]. It is known that GPCRs are involved in Ca²⁺ mobilization, the functioning of Ca²⁺ channels, and exocytosis of Weibel–Palade bodies [19][20], ultimately enhancing platelet adhesion and aggregation.

The persistence of severe microhematuria 24 hours after ULT, despite the administration of etamsylate, is presumably due to inhibition of platelet COX activity caused by the use of non-selective NSAIDs. The effectiveness of etamsylate in hemorrhages associated with COX inhibition remains poorly studied. One of the key challenges in interpreting its action is the lack of research on the plasticity of platelet signaling pathways in varying degrees of hematuria, which complicates the search for optimal mechanisms to enhance thrombogenesis and the development of new hemostatic drugs. A study of platelet functional regulation mechanisms during hematuria persisting for 24 hours has made it possible to identify a cluster of receptors involved in compensatory platelet aggregation during COX inhibition induced by NSAIDs. Enhanced signal transduction through receptors coupled to Gq-protein (PAF receptor), Gq- and G12/13-proteins (TP receptor), as well as Gi- and Gq-proteins (P2Y receptors) is considered a stereotypical mechanism for activating platelet aggregation [21–23]. The activation of compensatory platelet aggregation mechanisms during persistent postoperative hematuria may be driven by paracrine effects of activated leukocytes producing PAF (e.g., under pyelonephritis conditions), restoration of TxA2 synthesis (as a result of residual COX activity), and increased ADP concentration caused by purine nucleotide transformation during ischemia/hypoxia of the urinary tract tissues [24–26].

Systemic administration of etamsylate was accompanied by modulation of signaling pathways involved in the implementation of compensatory platelet aggregation mechanisms. The enhanced pro-aggregatory effect of etamsylate observed after the 4th dose (administered 30 hours post-ULT) is associated with increased stimulation of PAF and TP receptors, likely leading to optimization of intracellular platelet signaling. Since the Gq-protein–linked mechanism of platelet activation is common to the function of P2Y, TP, and PAF receptors, it can be assumed that the hemostatic effect of etamsylate also involves signaling pathways mediated by Gi-protein. Furthermore, the synergism of ADP, TxA2, and PAF [27][28] in implementing the pro-aggregatory effect of etamsylate cannot be excluded.

Indirect evidence supporting this hypothesis includes changes in the cluster of functionally active platelet receptors during persistent postoperative hematuria, possibly related to phenotypic reprogramming of circulating platelets during megakaryocytopoiesis.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The lack of randomization and a control group limits generalizability. These pilot findings apply to patients with persistent macrohematuria post-antegrade ULT unresponsive to three doses of etamsylate. Further multicenter controlled studies are needed. Monitoring GPCR-mediated platelet signaling could support personalized hemostatic therapy.

CONCLUSION

One-third of patients experienced persistent macrohematuria 24 hours post-antegrade ULT despite etamsylate. In these cases, enhanced Gq-mediated receptor signaling (PAF), co-activation of Gq/G12/13 (TP), and Gi/Gq (P2Y) pathways were observed. Etamsylate’s in vitro hemostatic effect was linked to GPCR signal integration, evidenced by increased platelet aggregation parameters (amplitude, slope, AUC). Maximum aggregation occurred with etamsylate–ADP synergy, indicating optimized Gi/Gq signaling.

AUTHORS CONTRIBUTIONS

Edward F. Barinov developed the study conception and design, performed the data analysis, and contributed to the editing of the manuscript. Dina I. Giller conducted aggregometry studies, carried out a literature review, and prepared the manuscript text. Sabina A. Akhundova performed in vitro receptor interaction modelling and the statistical data analysis. All the authors approved the final version of the article.

ВКЛАД АВТОРОВ

Э.Ф. Баринов разработал концепцию и дизайн исследования, проводил анализ полученных данных и редактирование рукописи. Д.И. Гиллер проводила агрегатометрические исследования, обзор литературы и подготовила текст рукописи. С.А. Ахундова моделировала in vitro взаимодействия рецепторов, проводила статистическую обработку данных. Все авторы утвердили окончательную версию статьи.

1. Clinical Guidelines “Urolithiasis” by the Russian Society of Urology, 2024. https://cr.minzdrav.govu/view-cr/7_2 (access date: 10.10.2024).

References

1. Giulioni C., Castellani D., Somani B.K., et al. The efficacy of retrograde intra-renal surgery (RIRS) for lower pole stones: results from 2946 patients. World J Urol. 2023 May; 41(5): 1407–1413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-023-04363-6. Epub 2023 Mar 17. PMID: 36930255

2. Škiljić S., Nešković N., Kristek G., et al. Point-of-care diagnostic approach in a critically ill patient with severe bleeding from urinary tract. Acta Clin Croat. 2023 Jul; 62(Suppl2): 138–142. https://doi.org/10.20471/acc.2023.62.s2.20. PMID: 38966024

3. Hashemzadeh M., Haseefa F., Peyton L., et al. A comprehensive review of the ten main platelet receptors involved in platelet activity and cardiovascular disease. Am J Blood Res. 2023 Dec 25; 13(6): 168–188. https://doi.org/10.62347/NHUV4765.eCollection 2023.PMID: 38223314

4. Bosilah A.H., Eldesouky E., Alghazaly M.M., et al. Comparative study between oxytocin and combination of tranexamic acid and ethamsylate in reducing intra-operative bleeding during emergency and elective cesarean section after 38 weeks of normal pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023 Jun 12; 23(1): 433. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-023-05728-w. PMID: 37308871

5. Razak A., Patel W., Durrani N.U.R., Pullattayil A.K. Interventions to reduce severe brain injury risk in preterm neonates: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Apr 3; 6(4): e237473. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.7473. PMID: 37052920

6. Gardner J., Husbands E. Medical management of refractory haematuria in palliative patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2024 Nov; 68(5): e404–e408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman. 2024.07.023. Epub 2024 Jul 29. PMID: 39084409

7. Herrería-Bustillo V., Masiá-Castillo M., Phillips H.R.P., Gil- Vicente L. Evaluation of the effect of etamsylate on thromboelastographic traces of canine blood with and without the addition of heparin. Vet Q. 2023 Dec; 43(1): 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/01652176.2023.2260449. Epub 2023 Sep 16. PMID: 37715947

8. Bhat A., Singh V., Bhat M., et al. Comparison of antegrade percutaneous versus retrograde ureteroscopic lithotripsy for upper ureteric calculus for stone clearance, morbidity, and complications. Indian J Urol. 2019 Jan-Mar; 35(1): 48–53. https://doi.org/10.4103/iju.IJU_89_18. PMID: 30692724

9. Lian S.L., Huang J., Zhang Y., Ding Y. The effect of plateletrich plasma on ferroptosis of nucleus pulposus cells induced by Erastin. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2024 Dec 24; 41: 101900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2024.101900. PMID: 39811190

10. Taguchi K., Hamamoto S., Osaga S., et al. Comparison of antegrade and retrograde ureterolithotripsy for proximal ureteral stones: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Androl Urol. 2021 Mar; 10(3): 1179–1191. https://doi.org/10.21037/tau-20-1296. PMID: 33850753

11. Stépanian A., Fischer F., Flaujac C., et al. Light transmission aggregometry for platelet function testing: position paper on current recommendations and French proposals for accreditation. Platelets. 2024 Dec; 35(1): 2427745. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537104.2024.2427745. Epub 2024 Nov 18. PMID: 39555668

12. El-Masry S.M., Helmy S.A. Hydrogel-based matrices for controlled drug delivery of etamsylate: prediction of in-vivo plasma profiles. Saudi Pharm J. 2020 Dec; 28(12): 1704-1718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2020.10.016. Epub 2020 Nov 6. PMID: 33424262

13. Mukherjee S., Sasmal P.K., Reddy K.P., et al. Spatiotemporally controlled release of etamsylate from bioinspired peptide-functionalized nanoparticles arrests bleeding rapidly and improves clot stability in a rabbit internal hemorrhage model. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2024 Aug 12; 10(8): 5014–5026. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsbiomaterials.4c00743. Epub 2024 Jul 10. PMID: 38982893

14. Garay R.P., Chiavaroli C., Hannaert P. Therapeutic efficacy and mechanism of action of ethamsylate, a long-standing hemostatic agent. Am J Ther. 2006 May-Jun; 13(3): 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mjt.0000158336.62740.54. PMID: 16772766

15. El Baser I.I.A., ElBendary H.M., ElDerie A. The synergistic effect of tranexamic acid and ethamsylate combination on blood loss in pediatric cardiac surgery. Ann Card Anaesth. 2021 Jan-Mar; 24(1): 17–23. https://doi.org/10.4103/aca.ACA_84_19. PMID: 33938826

16. Alvarez-Guerra M., Hernandez M.R., Escolar G., et al. The hemostatic agent ethamsylate enhances P-selectin membrane expression in human platelets and cultured endothelial cells. Thromb Res. 2002 Sep 15; 107(6): 329–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0049-3848(02)00353-5. PMID: 12565720

17. Cobo-Nuñez M.Y., El Assar M., Cuevas P., et al. Haemostatic agent etamsylate in vitro and in vivo antagonizes anti-coagulant activity of heparin. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018 May 15; 827: 167–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.03.028. Epub 2018 Mar 16. PMID: 29555505

18. Thibeault P.E., Ramachandran R. Biased signaling in platelet G-protein coupled receptors. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2021 Mar; 99(3): 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjpp-2020-0149. Epub 2020 Aug 26. PMID: 32846106

19. Woszczek G., Fuerst E. Ca2+ mobilization assays in GPCR drug discovery. Methods Mol Biol. 2015; 1272: 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-2336-6_6. PMID: 25563178

20. Naß J., Terglane J., Gerke V. Weibel palade bodies: unique secretory organelles of endothelial cells that control blood vessel homeostasis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021 Dec 16; 9: 813995. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.813995. PMID: 34977047

21. Obara K., Yoshioka K., Tanaka Y. Effects of platelet-activating factor (PAF) on the mechanical activities of lower urinary tract and genital smooth muscles. Biol Pharm Bull. 2024; 47(9): 1467– 1476. https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.b24-00440. PMID: 39218668

22. Capranzano P., Moliterno D., Capodanno D. Aspirin-free antiplatelet strategies after percutaneous coronary interventions. Eur Heart J. 2024 Feb 21; 45(8): 572–585. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad876. PMID: 38240716

23. von Kügelgen I. Pharmacological characterization of P2Y receptor subtypes – an update. Purinergic Signal. 2024 Apr; 20(2): 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11302-023-09963-w. Epub 2023 Sep 12. PMID: 37697211

24. Silva I.S., Almeida A.D., Lima Filho A.C.M., et al. Plateletactivating factor and protease-activated receptor 2 cooperate to promote neutrophil recruitment and lung inflammation through nuclear factor-kappa B transactivation. Sci Rep. 2023 Dec 7; 13(1): 21637. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48365-1. PMID: 38062077

25. Kishore B.K., Robson S.C., Dwyer K.M. CD39-adenosinergic axis in renal pathophysiology and therapeutics. Purinergic Signal. 2018 Jun; 14(2): 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11302-017-9596-x. Epub 2018 Jan 13. PMID: 29332180

26. Minuz P., Meneguzzi A., Fumagalli L., et al. Calcium-dependent Src phosphorylation and reactive oxygen species generation are implicated in the activation of human platelet induced by thromboxane A2 analogs. Front Pharmacol. 2018 Sep 26; 9: 1081. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.01081. PMID: 30319416

27. Honda N., Ohnishi K., Fujishiro T., et al. Alteration of release and role of adenosine diphosphate and thromboxane A2 during collagen- induced aggregation of platelets from cattle with Chediak- Higashi syndrome. Am J Vet Res. 2007 Dec; 68(12): 1399–1406. https://doi.org/10.2460/ajvr.68.12.1399. PMID: 18052747

28. Zhang J., Zhang Y., Zheng S., et al. PAK membrane translocation and phosphorylation regulate platelet aggregation downstream of Gi and G12/13 pathways. Thromb Haemost. 2020 Nov; 120(11): 1536–1547. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1714745. Epub 2020 Aug 27. PMID: 32854120

About the Authors

E. F. BarinovRussian Federation

Edward F. Barinov, Dr. of Sci. (Medicine), Professor, Head of the Department of Histology, Cytology, Embryology and Molecular Medicine

16, Ilyicha Ave., Donetsk, 84003

D. I. Giller

Russian Federation

Dina I. Giller, Assistant Professor, Department of Histology, Cytology, Embryology and Molecular Medicine

16, Ilyicha Ave., Donetsk, 84003

S. A. Akhundova

Russian Federation

Sabina A. Akhundova, Assistant Professor, Department of Histology, Cytology, Embryology and Molecular Medicine

16, Ilyicha Ave., Donetsk, 84003

Supplementary files

|

|

1. Графический абстракт | |

| Subject | ||

| Type | Исследовательские инструменты | |

View

(143KB)

|

Indexing metadata ▾ | |

|

|

2. Graphic abstract | |

| Subject | ||

| Type | Исследовательские инструменты | |

View

(139KB)

|

Indexing metadata ▾ | |

|

3. 1164_TREND checklist | |

| Subject | ||

| Type | Исследовательские инструменты | |

Download

(378KB)

|

Indexing metadata ▾ | |